A mind-bending recursive puzzle game about boxes within boxes within boxes within boxes. Learn to use infinity to your advantage as you explore a deep and elegant system.

⚠ Mild to moderate spoilers ahead! If you have not yet played Patrick’s Parabox, and wish to go in blind, please do not scroll any further.

What makes a good puzzle game? What does it even mean for a puzzle game to be good? How can you possibly compare Minesweeper with Portal, Sudoku with Sokoban? The world is rich with puzzle games across myriad genres. Of course, while one’s experience with a puzzle game – as with any other game – is deeply subjective, there are certain games out there that are undeniable special. They have some quirk, some brilliant quality about them, that elevates them above their contemporaries and/or similar games in their genre.

Over the years, I have noticed several aspects that all of the good puzzle games tend to share. They are innovative and thoughtfully designed, with mechanics that are “greater than the sum of its parts”, where complexity emerges from combining otherwise simple elements; where solutions are elegant and fresh; where creativity is rewarded. These qualities are by no means concrete, and one person’s good could well be another person’s bad. After all, many puzzle games augment their core experience with other characteristics such as witty narration, philosophical musings, pensive minimalism and/or a unique aesthetic. That said, putting eye candy aside and stripping a game back to its basics, it’s imperative that a puzzle game utilises its mechanics in a meaningful way in order to dazzle us with its “eureka” moments that us puzzle gamers ultimately crave.

I’m sure I can speak for most gamers in that I play puzzle games for the challenge; for the pure joy of problem solving, to experience that catharsis that comes from finding solutions to difficult puzzles, to live and breathe eureka. There’s a certain, ineffable elegance to this experience, like a beautiful proof in mathematics or executing a Fortran program without a segmentation fault. And so if I had to put a finger on what makes a puzzle game a true masterpiece, it’s one that’s full of discovery; one that keeps you glued to the keyboard. It should never feel stale or overly repetitive, and it most definitely should not feel like a chore to play.

The Sokoban Menagerie

Let’s talk about a somewhat niche sub-genre of puzzle games that has enjoyed high growth in recent years: sokobans. A sokoban (lit. warehouse-keeper) is a type of block-pushing puzzle game played on a grid (most commonly a square grid, though trigonal and hexagonal variants exist). At its core, a sokoban puzzle can usually be described as follows.

- The puzzle consists of an enclosed room, often irregularly shaped, and sometimes with internal walls, cavities and/or other movement-restricting barriers.

- Several movable blocks are scattered throughout the room, along with marked tiles indicating where the blocks must be placed (it doesn’t normally matter which specific block goes where).

- The puzzle is solved once the player has successfully placed a block on each marked tile. Sometimes the player also has their own marked tile to move to in order to close out the level.

- Blocks must be pushed and cannot normally be pulled. In the classic sokoban, blocks also cannot push other blocks.

This is, of course, just a basic formulation – one of many approaches to the genre. Just a handful of notable games that feature some innovative twists include:

- Sokobond (2014), where blocks are individual atoms (carbon, oxygen, etc), and levels are solved by bonding atoms together to form the desired molecules.

- A Good Snowman Is Hard To Build (2015), where you must stack snowballs to – you guessed it – build a snowman, in a manner somewhat akin to Towers of Hanoi.

- Stephen’s Sausage Roll (2016), a brutal game where you cook sausages.

- Baba Is You (2019), where blocks can be objects and instructions, which combine to create expressions (like BABA is YOU) that define the logic of the level itself. One of the best games ever made.

- Room To Grow (2021), where you play as a snake and can hence indirectly manoeuvre blocks by growing and contorting around the puzzle.

Today I shall discuss another such game that utilises a highly innovative mechanic all but redefining what it means to be a sokoban game. It is a game that is among the best puzzle games I’ve ever played.

Normal sokoban rules apply…

Patrick’s Parabox is what you get when you look at a typical sokoban game and ask yourself, “Wouldn’t it be funny if each block was its own mini-level.” As such, not only can you push blocks in Patrick’s Parabox, you can go inside them too. The fun, it turns out, doesn’t stop there. After all, every level is its own block. What happens when you push a level outside of itself? As Septimus Signus, talking about the Elder Scrolls, elegantly puts it:

Sometimes they even look up. What do they see then? What if they dive in? Then the madness begins.

– Septimus Signus, during Discerning the Transmundane, The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim

And Patrick’s Parabox is madness of the highest order. While it might seem like these special “paraboxes” are different to the regular blocks, the beauty of this game is that all these blocks are all essentially the same object; everything obeys the same rules.

The Beauty of Mechanics

Mechanics, at least on paper, do not define a game. They must be well implemented, well executed and well realised, and they mustn’t be too foreign to the player. Patrick’s Parabox has some of the purest mechanics I’ve ever seen, because it ultimately boils down to good old-fashioned sokoban with recursive blocks. Yet from this apparent simplicity comes a complex and brilliant array of puzzles. The game excels at not only introducing new gameplay mechanics, but by capitalising on their emergent properties.

Each level hub has its own name and theme, which is reflected in the design of that hub’s puzzles, often hinting at the type of solution that is needed. For example, “Reference” features puzzles involving traversing through multiple paraboxes – ultimately you need to know what level you’re on. “Swap” features puzzles whose solutions involve taking unravelling nested paraboxes. The puzzles in “Center” all take advantage of the fact that when you enter a parabox, you emerge in the middle along its central axis. “Fair enough”, you may think; only in later puzzles do the true implications, like anchoring a parabox by placing blocks to fill its central row/column, really set in.

What’s really special is that all of these gimmicks are inherent properties of paraboxes all along, it’s just that the previous puzzles have all been carefully curated to only introduce these new aspects further down the line. The mechanics were there to start with, simply hidden in plain sight. It’s such an elegant way to setup and design levels, for it means that the discovery of new mechanics occurs naturally while playing the game.

Puzzles Ought to Mean Something

Progression thus feels very meaningful as you are learning more about the game simply by solving puzzles. Many puzzle games – particularly minimalist games – tend not to explicitly explain new puzzle mechanics with text or animations and/or deliberately simple “tutorial” puzzles, and instead rely on the puzzles themselves as examples to learn from. It’s a trend that works especially well in Patrick’s Parabox because each new twist builds on prior knowledge, as opposed to being fundamentally distinct and unrelated. Contrast The Witness with its seemingly disparate mechanics that ultimately come together (such that in the cavern below the island the puzzles become second nature out of necessity), with the deliberate trial-and-error line puzzles of Understand, where its constant rule-changes stymie any sense of meaningful long-term progression. In general, shifting the burden of explanation onto the actual puzzles themselves is risky, potentially frustrating the player if it’s not immediately clear what’s going on (a common criticism of The Witness, for instance). At worst, this can completely destroy any sense of “eureka” once the player does stumble upon the solution. Reverse engineering is hard at the best of times. Patrick’s Parabox seems to keep this mind, with the first few puzzles in each region being carefully designed to introduce the new mechanical twist (while still being somewhat nontrivial to solve), from which harder puzzles follow. But it’s the fact that these puzzles all build on the puzzles before them that makes progression feel meaningful and worthwhile, which makes it all the more engaging to play.

This approach to introducing new mechanics that augment previous mechanics lends itself towards naturally emergent gameplay. With each new aspect comes more opportunities for creativity and complexity. I would be surprised if the developer had actually envisaged some of the late game puzzles when coming up with the concept. For me, playing this game and progressing through the puzzles was a case of “Oh wow, you can do this. Oh wow, that means you can do this!” And so on, and so on. (If the developer did have all these puzzles planned from the outset, then we are truly lesser beings undeserving of such skill). This is why the good puzzles games are truly good, for they exhibit this sense of exploration. Their puzzles – and their solution(s) – feel like they are discovered as opposed to feeling contrived and artificial.

The Joy of Well-Considered Design

I am by no means an expert on designing puzzles – making good puzzles is hard, as my experience in the Portal 2 level editor can attest to – but I am confident that I can recognise what works and what doesn’t. Let’s talk about one aspect that, depending on how it’s implemented, can come off as brilliant or lazy: repetition. Let’s illustrate this with some examples:

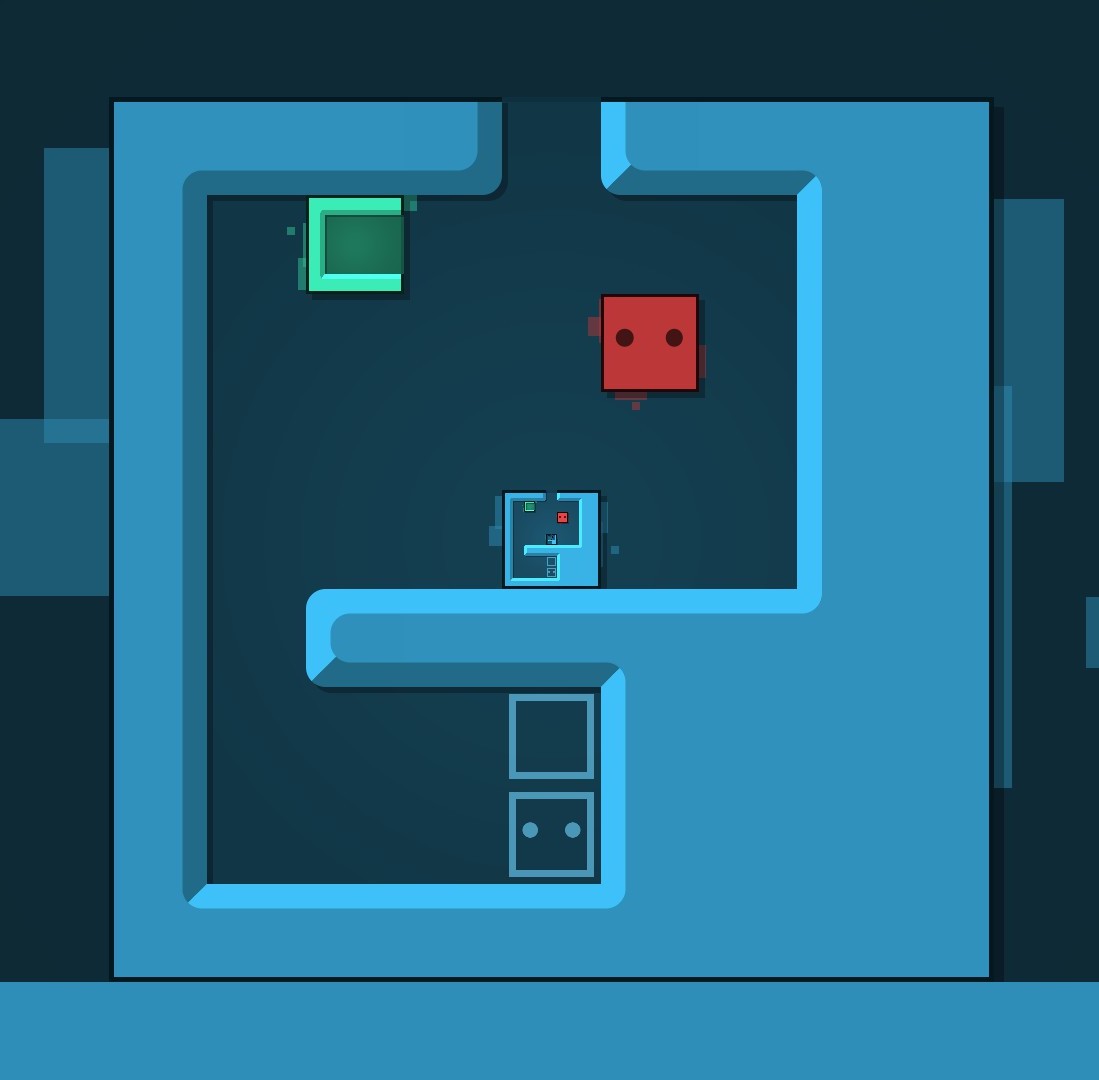

The two puzzles above share the same overall goal; you first have to put one block inside the other, then push it back out. Yet even though they look on the surface to be similar, the actual solutions vary significantly. In the left puzzle, you have to push both blocks out of the top half and into the bottom half, then push the blue block into the marigold box. If you attempt this same sequence of steps on the right puzzle you end up stuck, instead you must first push the blue block (which happens to be the level) into the aquamarine box. As for how to get the aquamarine box down from the ceiling… well, it’s all about perspective isn’t it?

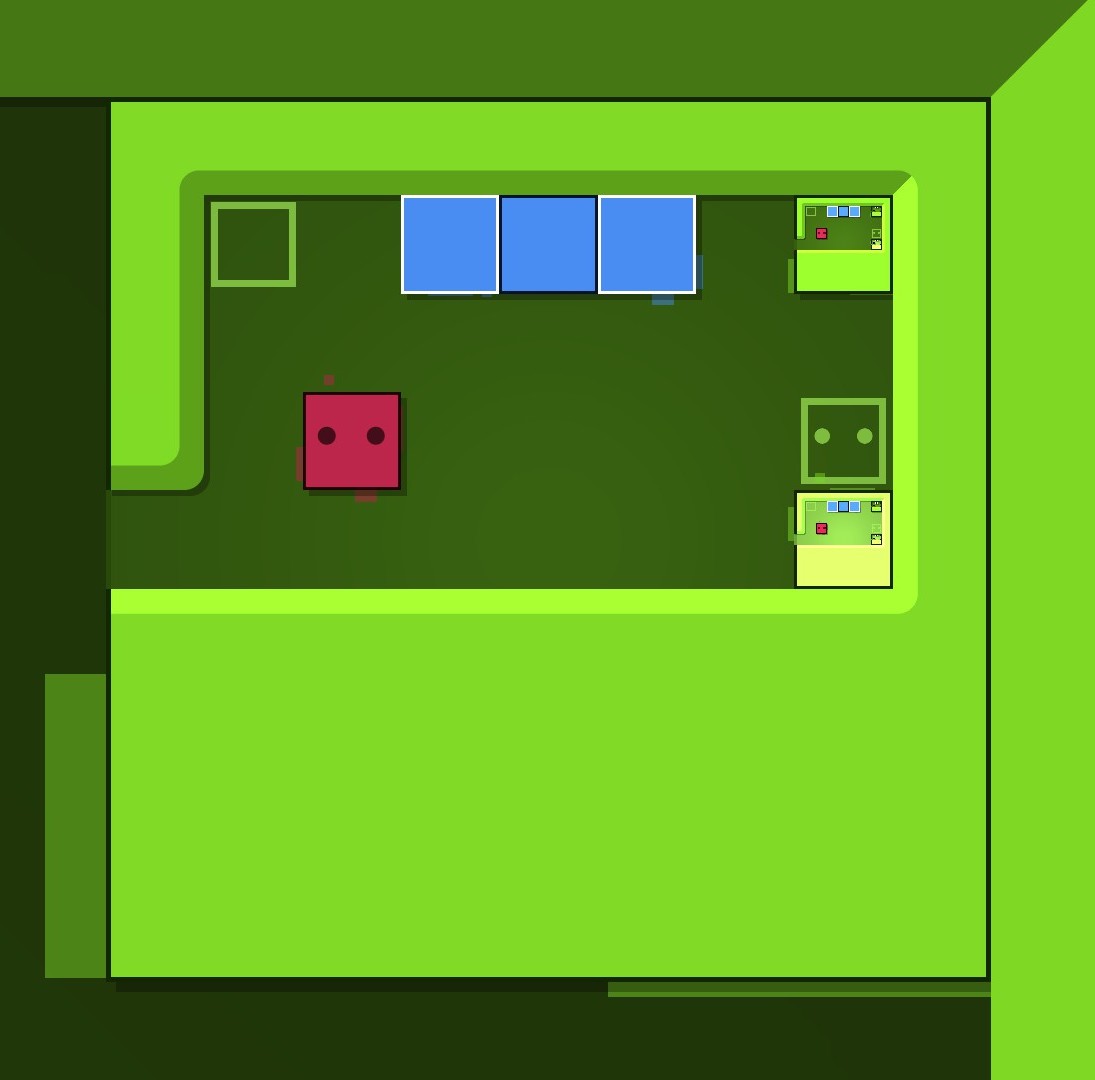

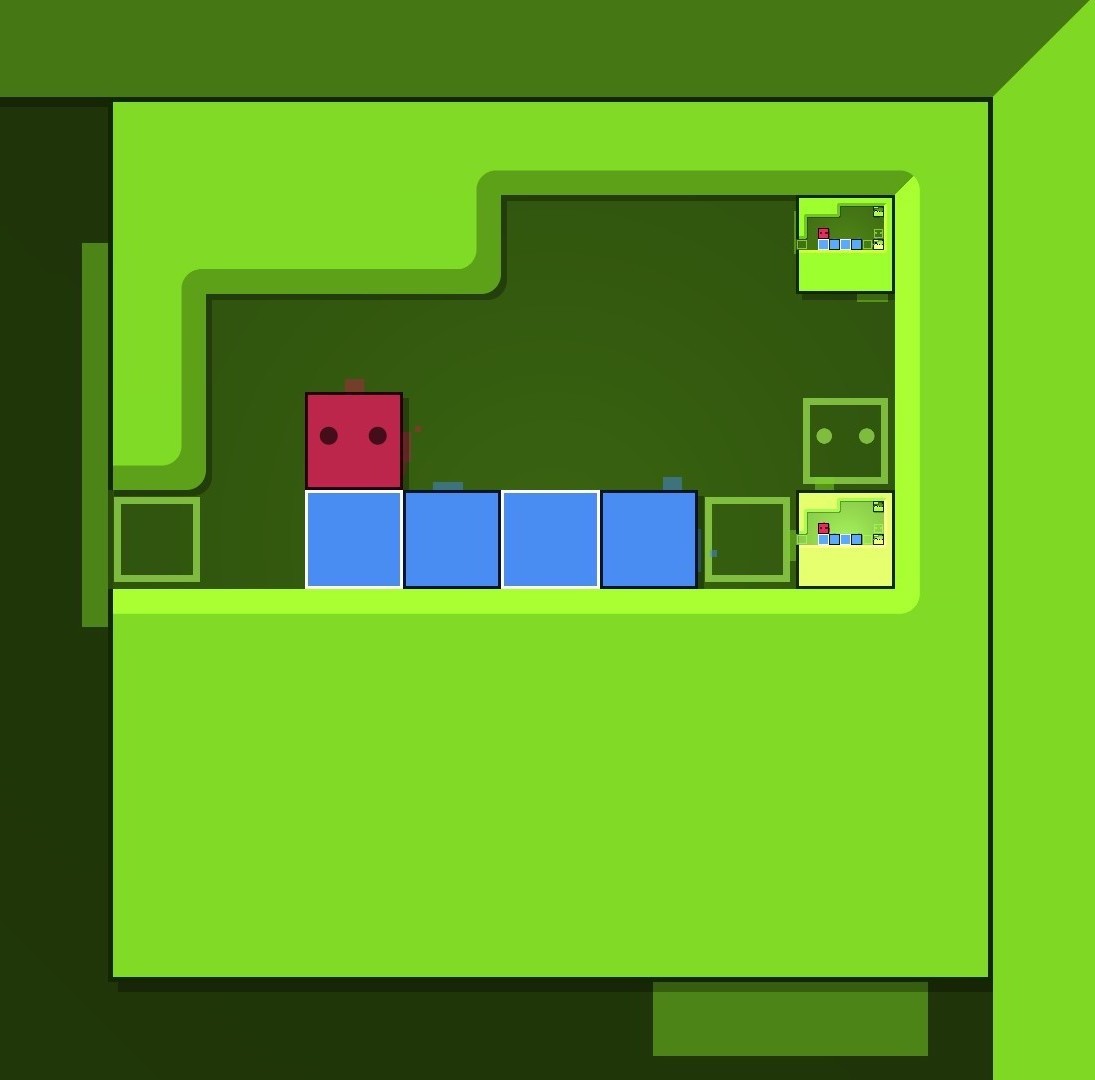

Here’s another pair of visually near-identical puzzles. As before, if you try to solve the one on the right with the same method as the one of left, you’ll have big problems. There is an art to designing a puzzle such that a few small tweaks can completely change the solution path. This is something Baba Is You does very frequently, and it’s a good way of forcing the player to change perspective and think of different solutions. It’s also an especially effective way to communicate the game’s mechanics to the player without an explicit tutorial.

Indeed, one of the issues that almost all puzzle games face – especially open ended ones – is how to manage their potential solutions. On the one hand is the intended solution (as envisaged by the level designers), but on the other hand are alternative solutions that may sometimes turn out to be much easier, such as by exploiting some shortcut, potentially even bypassing the eureka moment. Consequently, level design is a tricky balance in attempt to wall off certain exploits or “shortcut” alternative solutions, and instead hint the player towards the intended solution (or at least a non-trivial solution). This should never be overly direct, as the player deserves a sense of agency: railroading in puzzle games is never fun. At the same time, there should at least be some indication of what to do; things should not be overly obfuscated when a player is genuinely stuck.

There are two kinds of reactions I have when I’ve been stuck on a puzzle for a while and then eventually find the solution. It’s either “Are you serious? How was I supposed to know that?!” or “Wow, I’m stupid.” The key to great level design is to evoke the latter response, usually through those eureka moments where things all magically come together. The former response usually arises when the mechanics are so obscure that nothing shy of brute force is able to arrive at a solution, or when a puzzle is deliberately obfuscated for the sake of artificial difficulty. Any eureka that puzzle had to begin with is lost in the grind needed to achieve it.

Eureka

Patrick’s Parabox excels at eureka moments. It’s a testament to its strong, thoughtful level design, and its emergent gameplay mechanics. Ledges, cavities, the blocks themselves, all of these are usually there for a reason. Sure, there are the occasional red herrings, but for the most part the solution really is right in front of you. Many puzzles can be solved by just changing tact. Almost all the times I’ve been stuck on one was because I was repeatedly trying the same thing, unable to see the forest for the trees.

The game is no cakewalk; the designer explicitly mentions this in the game, stating that the puzzles are not meant to be solved quickly. According to howlongtobeat, the median completion time for all play styles is around 10 hours, with a completionist run taking upwards of 15 hours. This is on the long side for minimalist puzzlers, which are generally less than 5 hours. Although the game has a sequential structure, it’s not strictly linear; players are not required to complete every single puzzle in a hub before moving on to the next set of levels. In practice, this allows for the challenging puzzles to be optional, yet the game still entices you to solve these for the sake of achievements.

The only criticism I have of the game is that there are so many new mechanics that it can feel like a whirlwind to go through. While the game is relatively long as it is, I feel it could have benefited with a few more levels. Many hubs feature some gimmicky levels, such as a few where you have “friends” that mirror your movements, a few with irregular, rectangular tiles, and also some in ASCII graphics. These are quite short and have this showcase quality to them, as if their purpose is to serve as a demonstration rather than as a core part of the puzzle experience. These side-puzzles could have been more fleshed out, or at least incorporated more into the main puzzles. It’s a little disappointing to see a cool mechanic in only a few puzzles, only to never be seen again (though as for the side puzzles with the constant zooming in/out, good riddance!)

In Conclusion

Great puzzle games are few and far between, and I’m happy to recommend Patrick’s Parabox as one of this year’s standout games. Not only is Patrick’s Parabox an outstanding technical achievement, but it is also a shining beacon of great puzzle design and emergent mechanics, containing far more surprising eureka moments than your typical minimalist puzzler.