Spoilers for The Witness and Taiji ahead!

Unless otherwise stated, all screenshots are from my own gameplay.

Pen and paper logic puzzles have this strange, alluring quality about them. They might not look like much but they’re surprisingly easy to get hooked on. There is even a dedicated world puzzle championship boasting all manner of esoteric grids and rules.

Take, for example, Sudoku, one of the more “mainstream” logic puzzles. Any half-decent newsagent will undoubtedly stock dozens of mass-produced Sudoku books on 50gsm recycled paper, chock-full with hundreds of partially-filled grids. Don’t get me wrong, I enjoy the odd Sudoku or two. But I’ve always felt a sense of cold austerity when it comes to books like these. There is something inherently robotic – dangerously mundane – when it comes to trudging through grid after grid. Contrast this with the lovingly hand-crafted Sudoku puzzles featured on Cracking the Cryptic, where the sheer joy (and terror) on the face of the solver is priceless, if not outright inspirational.

Now, if it’s all just numbers on a grid, then how can logic puzzles elicit such passionate responses?

How can some puzzles feel more joyous and meaningful than others?

How can monotony give way to awe?

Abstract Line Puzzles

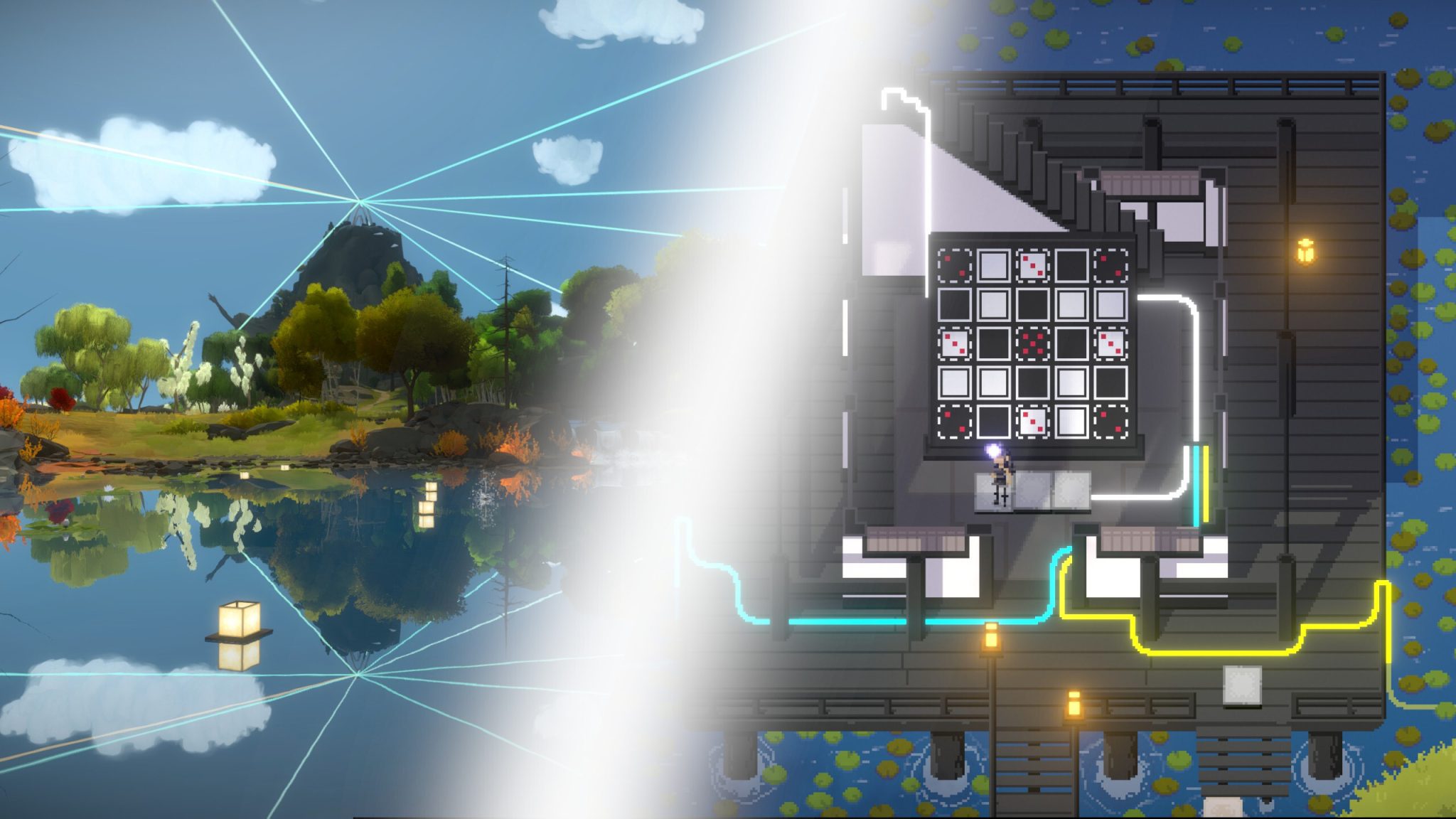

Jonathan Blow’s The Witness, released in 2016, is an open-world puzzle game. At least, that’s what it looks like if you just happened to stumble upon it while browsing the Steam store. The central premise goes something like this:

You find yourself on an island littered with puzzle panels. Each panel is essentially a grid-based line puzzle. You must draw a path on the grid between designated “start” and “end” points that satisfies the rules of the puzzle.

To be read in the narrator’s voice from Slay the Princess.

“Simple enough”, you might quip. Indeed, this is perhaps why The Witness evokes a polarising range of reactions. You could, with arguably good reason, dismiss the game entirely as just a scenic walking simulator, nothing more than a “Firewatch with line puzzles”. You could also turn around and declare The Witness a masterpiece on contemplation, meditation and zen. Joseph Anderson calls it “a great game that you shouldn’t play”. Shortly after fully completing the game, I offered a rather tacit yet unenthusiastic recommendation on Steam, cautioning that much of the meaning of the game comes from what you, as the player, make of it. Even then, if The Witness is truly just another “puzzle game”, why have countless blog posts and video essays been written about it? Are such ruminations rooted in something deeper?

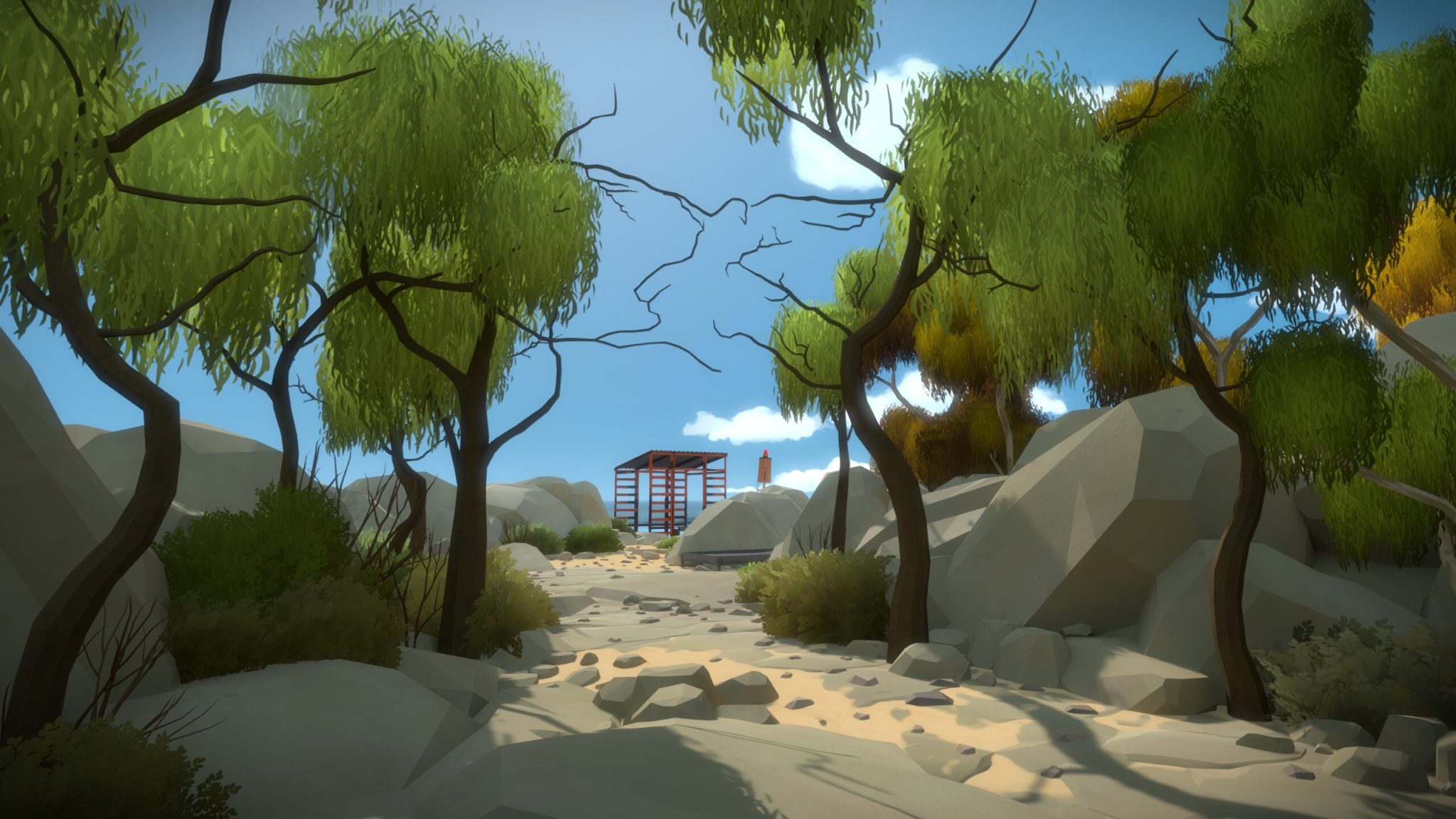

To explore this, let’s first talk about the puzzles themselves. The Witness’ island is partitioned into strikingly different zones that we may as well refer to as biomes. From lush bamboo forests to sun-kissed deserts, the biomes are strikingly distinct and richly presented, crafted with such perfection that you could easily take a picturesque screenshot from just about any spot on the island. Within each biome, the puzzles all take on a specific theme (or sometimes multiple themes). This could be a particular rule mechanic tied to an explicit symbol, or perhaps tied into a broader, contextual hint. Almost every location is accessible right from the get go, so there’s no real set, linear order. That said, some areas contain a mixture of puzzle mechanics, and so are therefore best saved till last.

Line puzzles on a grid couldn’t possibly be that complicated, right? Well, as far as puzzle mechanics go, there is a surprising amount of variety (and complexity). Some puzzles feature stars that must be isolated into groups of no more than two of the same colour (a nod to the logic puzzle Star Battle). Some panels feature groups of triangles, whereby the number of triangles in a given cell denotes the number of its edges that your path must traverse (a nod to Slitherlink). Some feature tetrominoes, whose combined shape(s) must be traced out by your solution. There are also many puzzles that don’t feature any symbols at all, but are instead solved through contextual cues, usually related to the environment. For instance, the solution may be inferred from the relative heights of seemingly innocuous objects in the background, or revealed by looking at the light reflected off of the panel itself. In some cases it’s as simple as the path up a tree.

At this point, it should probably go without saying that players who aren’t massive fans of logic puzzles – let alone line puzzles – will likely find it hard to stay motivated given the sheer number of panels scattered around the island. It’s not so different, on paper at least, to those giant mass-produced, computer-generated Sudoku Puzzle books I alluded to at the start of this very post. After all, drawing lines is the only gameplay mechanic that The Witness has to offer. Now, if all you wanted to solve a bunch of abstract line puzzles, you could just play a bunch of Slitherlink, Star Battle and/or Masyu puzzles online (or, for the dedicated connoisseur, purchase a puzzle book directly from Nikoli). Surely there must be more going on here that meets the eye.

Before we get to that, it’s worth spending a bit more time talking about the puzzles. Although the rather repetitive nature of The Witness’ puzzles is a common theme amongst its negative Steam reviews, it is far from the only source of consternation. This is since the rules of the puzzles are never explicitly taught, only hinted at by (simpler) example puzzles. It is up to you to infer the rules of the puzzles from these limited examples. If you can, more power to you. But if you can’t, it’s more or less a…

Leap of Faith

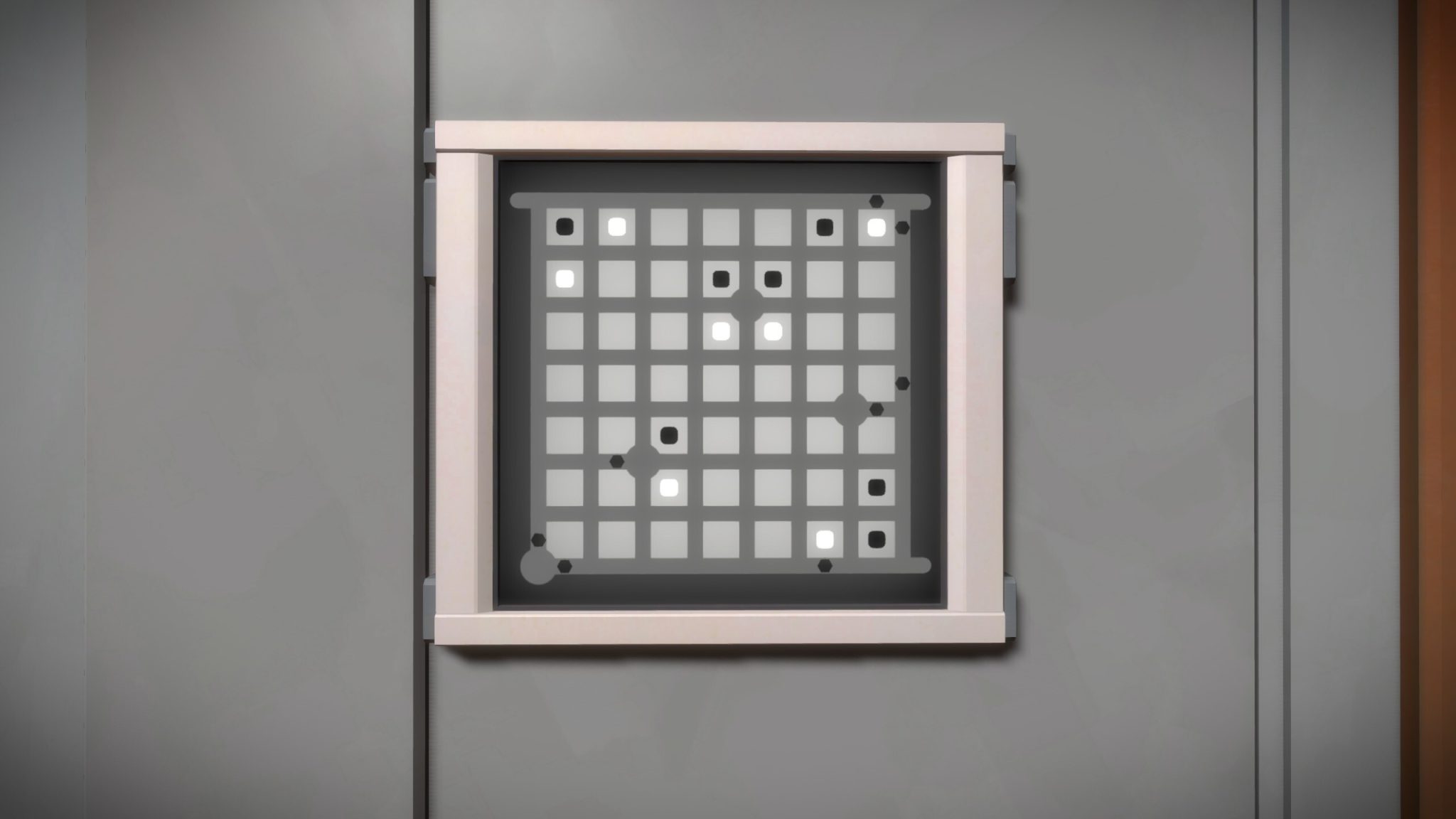

Just outside the starting area, you will likely find the following door. It looks nothing like any of the panel puzzles a new player will have encountered so far (which have just been mazes). You could get lucky, but there are multiple starting points. How do you know where to even begin?

Head further down the path and you’ll find a series of easier puzzles. And, lo and behold, it’s the same symbols; black and white blocks. Upon solving these, you realise you may well have a shot at opening that blasted door. The two rules in this case – (1) partitioning the grid into regions with same-coloured cells; (2) the line should pass through every hexagonal dot – are never explicitly mentioned.

In tackling the easy puzzles, you are gaining the knowledge needed to tackle the harder puzzles. That’s the theory at least. This all might sound like stating the bleeding obvious; every modern puzzle game does this to varying degrees, and there are no shortage of players who relish the idea of tutorial-less puzzler. Fundamentally though, this idea of graduated difficulty is ultimately how we humans learn, right? You only have to look at any university-level textbook to see the same principle in action (Griffith’s Introduction to Electromagnetism being an egregious offender). But in order for this to actually work – for the players to actually learn the mechanics of the puzzles – the example puzzles need to be clear (Griffith’s Introduction to Electromagnetism, again, being an egregious offender).

There is an art to crafting good puzzles, as masterfully outlined in Elyot Grant’s definitive three-part series 30 Puzzle Design Lessons. That passionate “epiphany” you get when making a brilliant breakthrough solving a well-designed puzzle is often referred to as a Eureka moment, or an “a-ha!” moment. Think of that joy of realising how momentum works in Portal. That burst of raw emotion is what puzzle enthusiasts live for. Although the “tutorial puzzle” approach to puzzle game design is omnipresent, one major caveat that can often be overlooked is that it ultimately relies on a “leap of faith”. In fact, not just one leap of faith, but two: one from the developer, the other from the player.

The first leap of faith is the expectation (by the developers) that the player will actually encounter these Eureka moments; that they will join the dots and “discover” the mechanics for themselves. Clearly much of mid and late-game progression is conditional on the player having discovered the rules (e.g. The Witness‘ “town centre” is all but unsolvable if players are unfamiliar with several core mechanics). The second leap of faith – arguably the most important – is made by the player when they experience said Eureka moments, formulate their own theories about how the rules work, and subsequently assume it works everywhere.

When both these leaps of faith successfully intertwine, the pay off is enormous. There is no greater reward than the satisfaction of having figured something else by yourself, and the comfort of knowing that your interpretation of the rules is indeed correct. Yet on the contrary, it can be incredibly frustrating if the mechanics are too unclear, or if the “hints” are not properly communicated. As there’s often no explicit rulebook, there is no way for the player to tell how a puzzle mechanic actually works. The only feedback available to the player is knowing if their answer is right or wrong. Worse still – a player’s theory about a particular mechanic may work for the example puzzles, but completely break down in later puzzles. Since the outcome of a puzzle is the only form of feedback, it is very easy to arrive at misleading conclusions about the puzzle’s mechanics, and subsequently get stuck later based on this false understanding. The end result is a player fumbling in the dark, where the only practical way out is through brute force or, heavens above, a walkthrough. Not only does this completely nullify any sense of reward or satisfaction, but it can lead to further confusion and frustration.

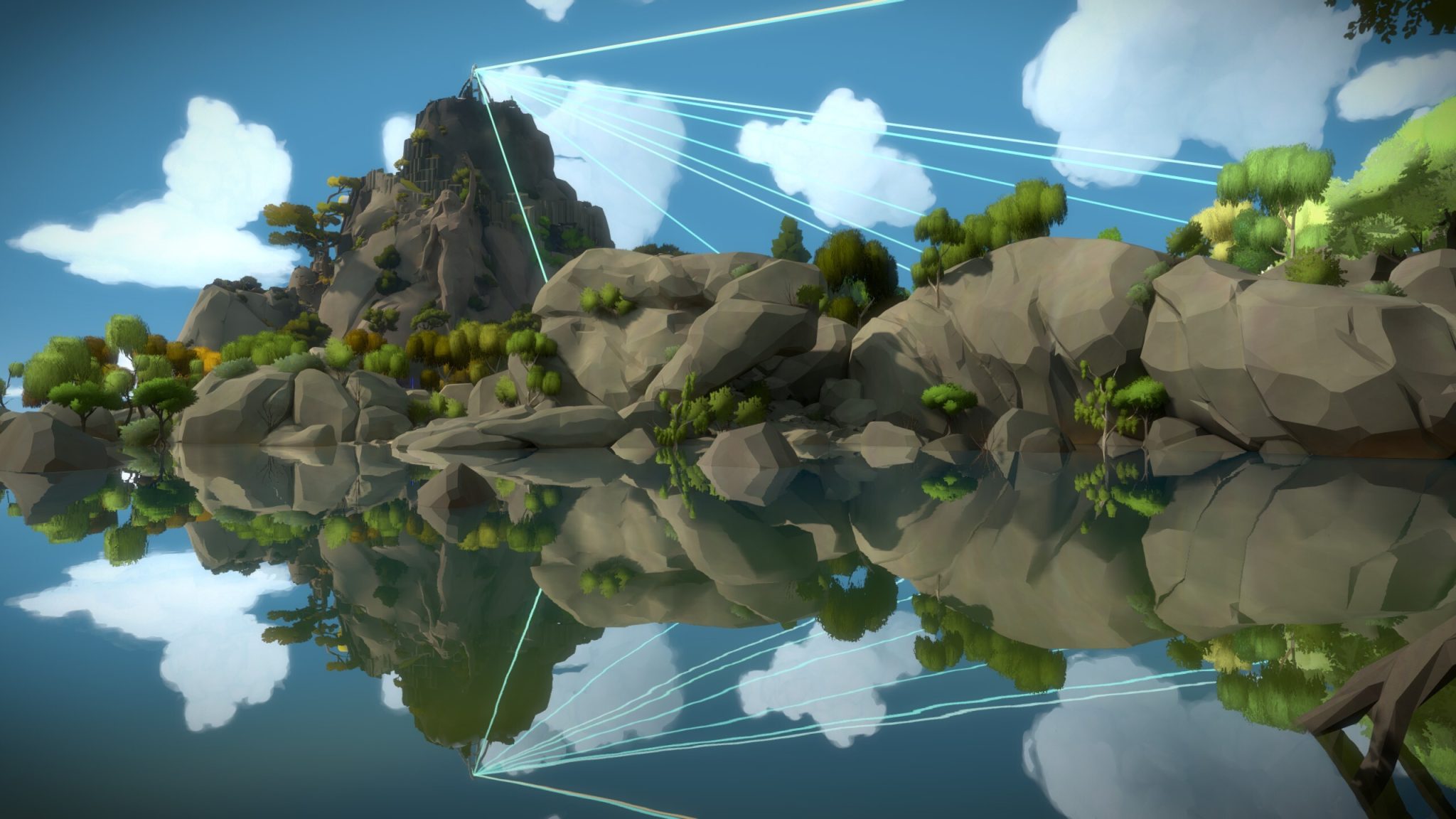

With that in mind, are The Witness’ puzzles good puzzles? Are they sufficiently stimulating such that solving them is a pleasurable, eye-opening experience? Except in one special setting that’s antithetical to the rest of the experience (more on that later), The Witness’ puzzles are merely panels upon panels to slog through just to complete the associated region and activate one more laser beam. Of course, not every puzzle has to be a thought-provoking gem, but there’s enough mundanity that solving them can quickly become a chore, if not for simply solving them for the sake of pleasure. Perhaps there is some deeper meaning to solving these puzzles, as if the methodical, repetitive process is meant to induce some sort of ASMR to unlock the way to nirvana. During my playthrough, there were times when I felt that I was simply spacing out and acting on autopilot, not really being conscious of the puzzles at all. At the start, The Witness doesn’t appear to have any story or overarching objective (other than activating the laser beams), so all you’re left with is the experience of solving puzzles whilst enjoying the fine scenery. The puzzles do come with a fair chunk of eureka moments. There were some parts that genuinely surprised me, but as a whole they were largely forgettable. As it turns out, there are other puzzles on the island. Puzzles other than drawing lines on a grid panel. These puzzles were far more memorable. Turns out enjoying the fine scenery has its dividends.

Apophenia

There is a moment that happens when playing The Witness when you realise that the panel puzzles are not the only places where you can draw lines. The canonical point at which a player makes this discovery – insofar as there is an actual puzzle panel that deliberately draws your attention to it – is atop the island’s mountain. Eager players may have discovered these environmental puzzles much earlier, such as by looking backwards immediately after exiting the starting tunnel, or noticing a certain alignment once out in the initial courtyard. The Witness’ environmental puzzles represent the biggest “a-ha!” moments the game has to offer. If the panel puzzles were ASMR, then these environmental puzzles are frisson. I’d even go so far as to say that these particular puzzles are what constitutes the real game; the real message. For you can easily be driven mad scrutinising every single piece of scenery, every wall, every flower, every reflection of the Sun, every conspicuous arrangement of objects that may just so happen to look like a circle and a line from a certain ideal angle.

Whether or not you, as the player, are enamoured by what effectively amounts to apophenia – or perhaps an increased degree of awareness of one’s surrounding – will determine whether you truly enjoy this aspect of The Witness. Because while most of these environmental puzzles are static (in that you simply need to stand in the right position and look in the right way), there are others that take time to setup and complete, such as the ones you can only complete by boat. Let’s not forget the especially notorious one in the movie theatre that takes an hour to complete.

Perhaps my unease when playing The Witness arose from feeling that my time was being unduly wasted, panel puzzles and all. And yet here I am, taking what has definitely been more than my total playtime, writing about The Witness; writing about symbols and motifs. Because The Witness is full of symbols, and these aren’t just stars, dots, triangles and tetrominoes. Go looking around the island and you’ll find many optical illusions, from tree branches to statues. There is an overwhelming emphasis on the notion of circle and line; of start and end; purpose and resolution; hardship and acceptance. We can go on and on ascribing any manner of philosophical duality to these shapes. So what, if anything, is The Witness trying to say? To get at least some semblance of an idea, one might consider a trip to the cinema.

A Phantom and a Dream

The most striking feature of The Witness that you will notice almost immediately after exiting the starting tunnel is its silence. Apart from a few special effects and ambient noise – the hum of the quarry, the roar of the waterfall, the gentle creak of the windmill, and approximately six and a half minutes of Edvard Grieg – the island is mostly silent. The island is kept in a state of uncanny stillness; the very same stillness one might experience when perusing through an art gallery or a sacred memorial garden.

So, imagine my surprise when I found that there is a small cinema hidden beneath the town (a Talos Principle reference perhaps?). In true puzzle game style, it is the devious off-the-beaten-track puzzles (like that imposing door to the bunker outside the starting area) that must be solved in order to gain access to special codes that, when entered into the control panel in the theatre, unlock some films. Altogether there are six films, which are a complete mixed bag, but they all offer their own unique take on meaning. Or at least, how one can come to find meaning.

James Burke espouses the virtue of absolute, objective truth above all else, going so far as to criticise the humanities and arts for their inherently subjective interpretations of the world, while instead advocating for hard, scientific knowledge.

As a somewhat more tempered point of view, renowned physicist Richard Feynmann speaks candidly about what it is that drives his curiosity: the desire to simply find out more about the world. However, it is not just the desire to ask questions that’s important, but also to understand – and accept – the limits of their answers.

“I think it’s much more interesting to live not knowing than to have answers which might be wrong.”

Richard Feynmann

Rupert Spira’s talk – which gives Septimus Signus a run for his money – ascribes a great deal of importance to one’s presence of awareness. Non-judgemental, non-reactive, it’s the part of us that simply observes… the part of us that witnesses.

“Sensations, or the body, can be agitated. The world can be agitated. But what about you, the one that knows the apparent mind, body and world? Can you, this open empty presence, be agitated?”

Rupert Spira

In this sense, meaning comes not from the world (or rather, from external influences), but rather from deep within you. It’s worth noting that Spira’s philosophy of non-duality is closely related to the teachings of the Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism, specifically the concept of Sakshi: pure awareness; the “Witness Consciousness”. Gangaji offers an even more direct argument, challenging viewers to “stop looking for what you want”, asserting instead that “more than what can be wanted is already who you are.” Now, I can’t personally see myself subscribing to the whole New Age self-empowerment / “you are your own Universe” mindset, but I find its inclusion in The Witness to be interesting in the sense that it may as well be saying that you shouldn’t really bother finding meaning in external things, and that it is better to focus on your own meaning within.

The most compelling video out of all six is Brian Moriarty’s The Secret of Psalm 46, an hour-long speech about easter eggs, hidden meanings, and awe. In order to access the code to unlock it, you have to complete a certain challenge.

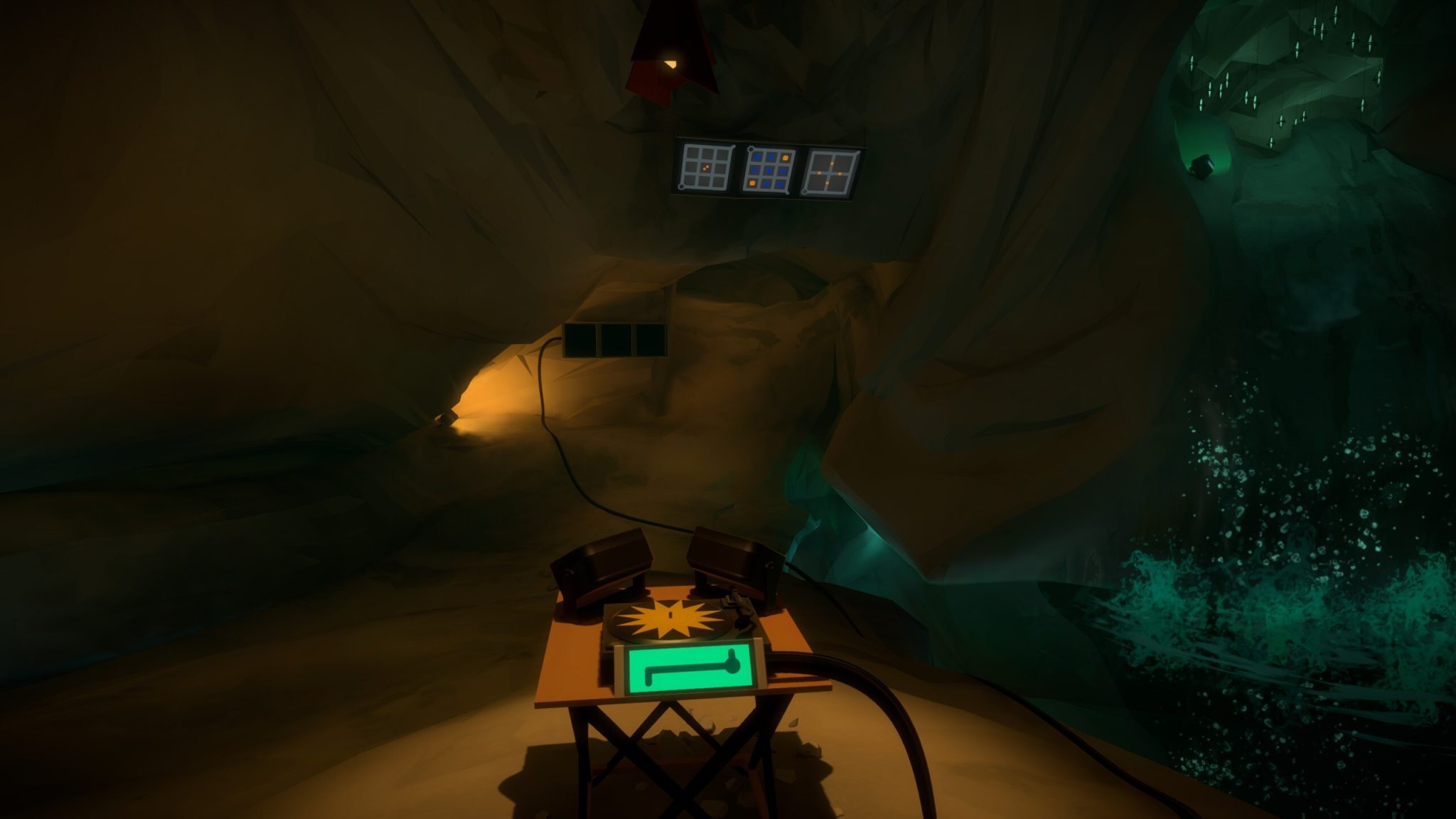

Deep in the bowels of The Witness’ mountain lies a secret cavern, accessible only by activating all laser beams. Inside that cavern is a pillar puzzle that unlocks another cavern, which houses the most difficult part of the game.

To be read in the narrator’s voice from Slay the Princess.

The “challenge” is a timed gauntlet of randomised puzzles, divided into several sections with fixed puzzle types. You have the combined length of Anitra’s Dance and In the Hall of the Mountain King from Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 (around 6 minutes and 30 seconds) to complete all the puzzles. The key to defeating this challenge is instinct. You don’t have time to peer over each puzzle. You have to trust in your ability to solve them naturally. It will likely take multiple attempts. You will likely contemplate giving up. You may even have to adjust the FOV slider and/or puzzle line speed in the settings.

To lift the terminology from Elyot Grant, what the “challenge” offers is pure “fiero”. The experience is so jarringly different to the rest of the game that it begs the question as to why it’s even included. Indeed, the fact that The Secret of Psalm 46 is the player’s reward upon completion, is clearly no mistake. The talk is heavy, its ruminations heaped with allegory, and anything I write here cannot possibly come close to doing it justice. But while it instills that raw power of awe that comes with well-hidden secrets, one of the key warnings of The Secret of Psalm 46 is to beware the self-ruinous quest for finding meaning where there is none, lest one become “lost in a labyrinth of delusion, mining order from chaos.” Because of course that’s the reward. The Challenge is simply The Challenge. The Witness is simply The Witness.

There is another film clip that shows the ending scene from Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1983 film Nostalghia, in which a man attempts to transport a candle from one end of a pool to another, ensuring it remains lit the entire time. After several failed attempts he finally succeeds, only to promptly die thereafter. It’s a scene that Tarkovsky intended to “display an entire human life in one shot, without any editing, from beginning to end, from birth to the very moment of death.” It is a hauntingly beautiful piece of cinema, and I can see why it fits the whole theme of The Witness. Is there any meaning or purpose to transporting candles? Is there any meaning or purpose to solving a puzzle? There’s nothing to say that we have to solve these puzzles. Yet somehow – almost on instinct – we do.

For as much as The Witness has to offer in terms of philosophical musings, the player is not exactly left with any concrete substance to make of it, and ultimately leaves the games with more questions. The only semblance of a story is the fact that the island is actually a virtual reality simulation, which you exit via the secret (true) ending. The final cutscene shows the player stumbling through an empty house battling the sensory overload thanks to a heightened sensitivity to circles (akin to suffering from the Tetris effect). Now, I couldn’t help but be drawn to the fact that there is another puzzle game that takes place in a simulated reality and which isn’t shy to positively bombard the player with heavy philosophical musing. Indeed, Croteam’s 2014 gem The Talos Principle gifts its players with a much more substantial story (surpassed by even greater heights in its 2023 sequel), from which its purpose and philosophical messages are better comprehended through not just the player’s actions but also through the context of its worldbuilding. By contrast, The Witness feels more like a tabula rasa, where any meaning comes from the player and their interactions with the game. For this reason, The Witness can perhaps be more aptly described as a meta-philosophical game. Which is probably by design.

The Imposter

A discussion of The Witness post-2022 is not complete without mention of The Looker, a short free-to-play parody game. As a parody, it nails everything on the head. I won’t spoil anything, suffice to say that if you were a little frustrated and annoyed with The Witness’ vague notions of enlightenment, you’ll be in for a short but rewarding treat.

It’s fair to say that my impressions after initially completing The Witness were lukewarm. However, in the years since, after playing a certain other abstract puzzle game, I have come to look back on The Witness with ever greater appreciation. The spark that reignited that interest – and which ultimately led to me deciding to write this very post – was Taiji.

Abstract Grid Puzzles

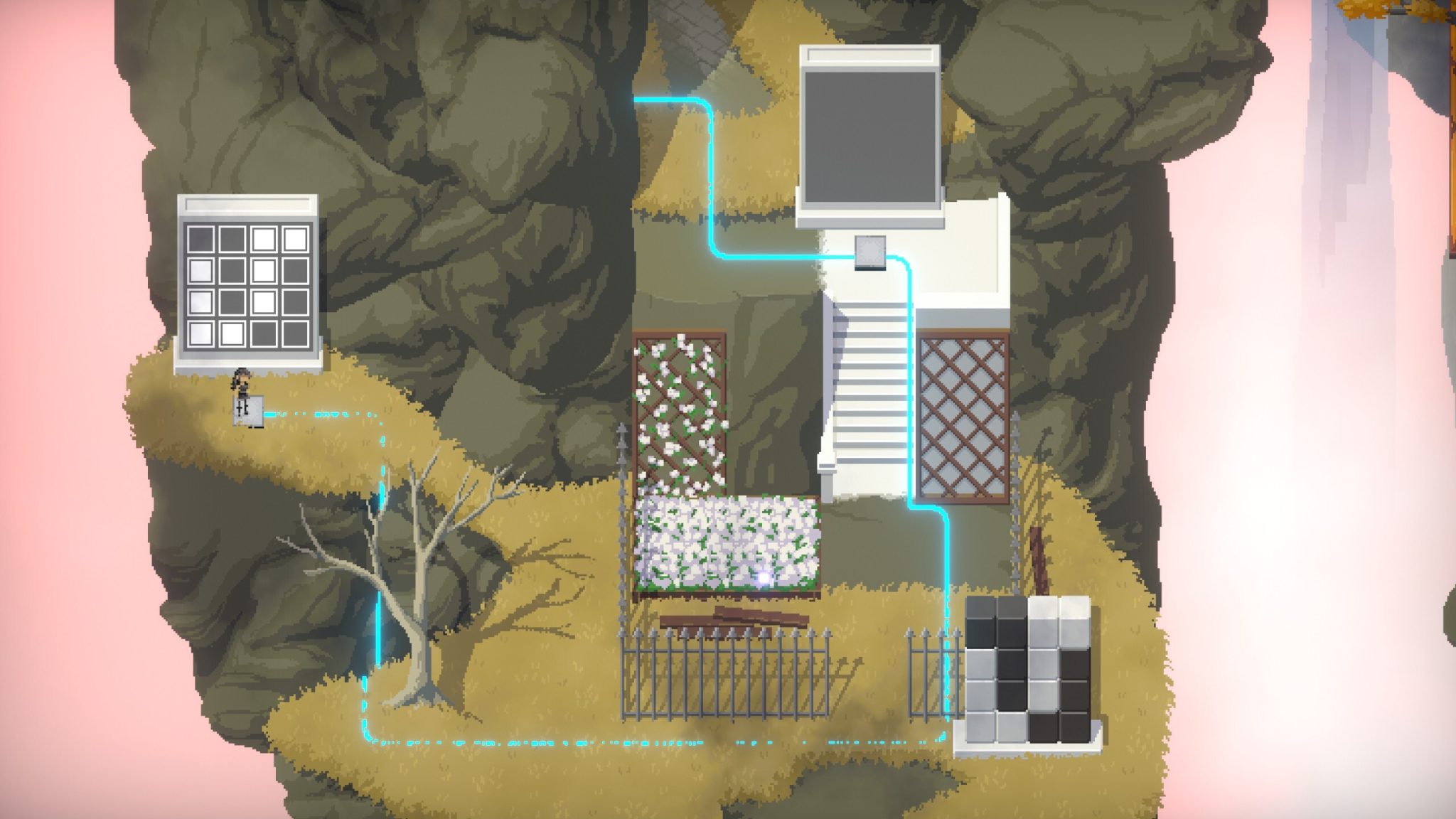

At a first glance of its store page, Taiji looks very much like a carbon copy of The Witness, albeit in a 2D pixel art form (though it’s worth noting that Taiji was in-development before The Witness released and is very much its own game). After all, consider the game’s premise:

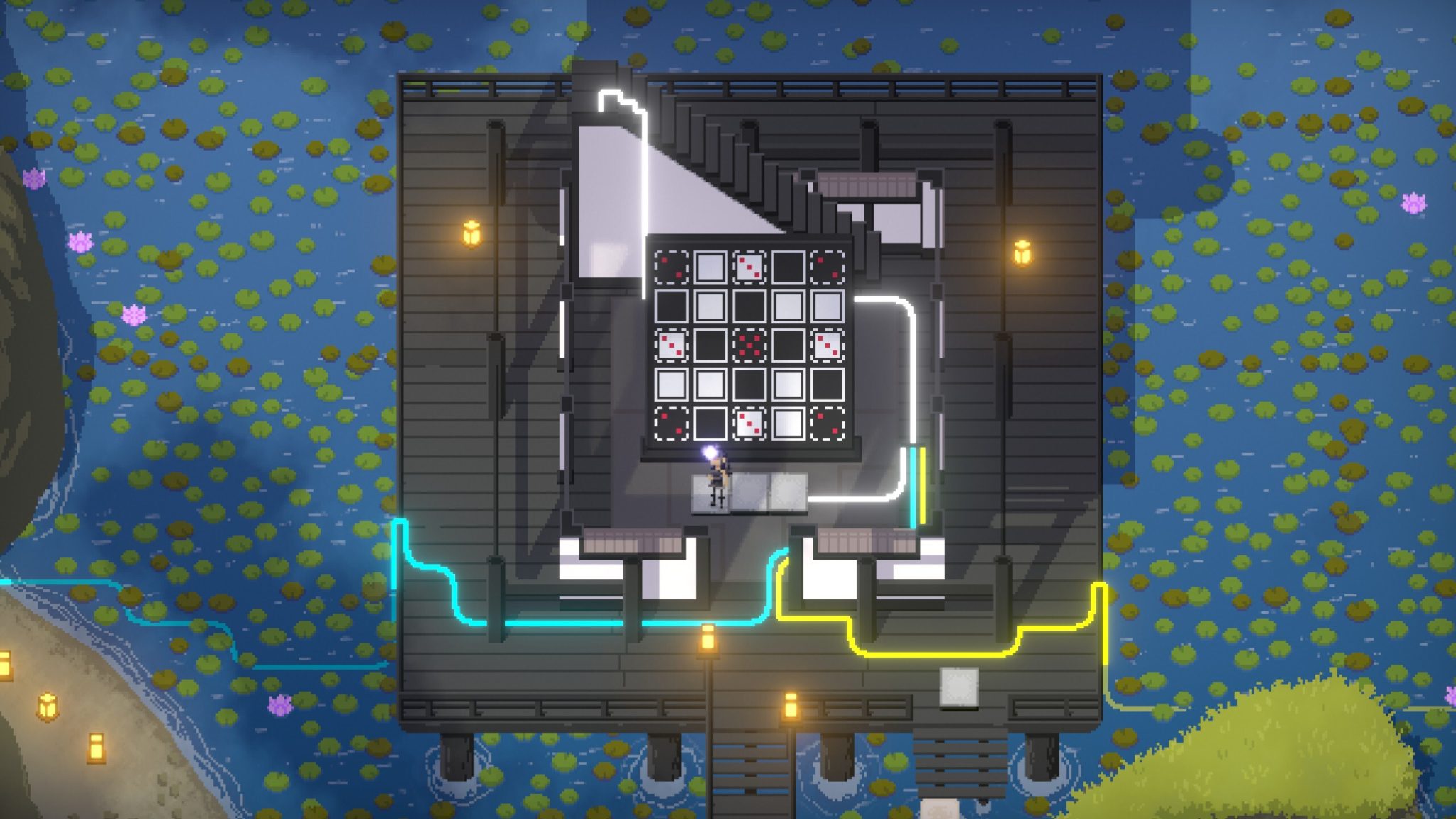

You find yourself on an island surrounded by panel puzzles. Each panel is effectively a grid-based tile puzzle. You must toggle individual tiles on/off in order to draw a pattern that satisfies the rules of the puzzle.

To be read in the…

Now, in most cases you merely click on the tiles, but there are some puzzles in which you must physically walk-out a path with your character (just like the maze puzzles in The Witness’ castle). Taiji’s island is divided into strikingly different biomes; the puzzles in each region are mostly characterised by a unique rule or mechanic, indicated by a unique symbol. Almost every location is accessible right from the get go, so there’s no real set, linear order. That said, some areas contain a mixture of puzzle mechanics, and so are therefore best saved till last. Hang on, that all sounds oddly familiar.

When I played Taiji, I had an epiphany. I suddenly understood what The Witness was supposed to be (or rather, what I was supposed to have felt while playing it): the fusion of symbol and motif. It’s the experience of taking a step back; the experience of contemplation; the experience of witness consciousness. Playing Taiji was a profoundly meditative experience. Obviously a soft piano, oriental zither and gorgeous pixel art is what I needed to finally see. In contrast, maybe the sheer silence of The Witness’ world was, in its own way, deliberately deafening. It is probably no accident that playing Taiji was the catalyst for my newfound appreciation of The Witness. After all, Taiji‘s lead developer cites The Witness as a key source of inspiration, and its motifs and design philosophy are firmly printed in the game.

The Void of Apparent Meaninglessness

Joel Goodwin’s brilliant “The Unbearable Now” is a fascinating commentary on The Witness that raises an interesting point, positing that it is our instinct – our very human nature – to resist the urge to “pause”. Perhaps that is the reason why I had that nagging sense of frustration while playing The Witness. The island is still. The island is quiet. Nothing makes sense. The island is surely meaningless. And maybe that is the point of The Witness: to fall into its trap of feeling like you have to ascribe meaning to everything in order for the whole experience to be worth your time; that the cursed fixation on finding “reasons to justify continuing to play” is so extreme that simply slowing down and seeing the game for what it is becomes unthinkable. The island is simply the island. The Witness is simply The Witness.

Paradoxically, Taiji manages to break through this “void of apparent meaninglessness” by virtue of its even greater abstractness (which is unsurprisingly easier to execute in a 2D medium). There’s no distractions. There’s no pretension to higher meaning, as The Witness would fool you into believing with its fustian audio logs, countless optical illusions and lying-in-plain-sight patterns. Taiji is simply an abstract island with abstract puzzles. And the gameplay and design that comes with said abstract puzzles is sublime. Taiji’s puzzles are a good lesson in “less is more”. As a whole, the puzzles are compact and generally faster to solve compared to those in The Witness. Thanks to there being a huge number of example puzzles for each gameplay element, solving them quickly becomes second nature (although this still does not necessarily guarantee that the player’s theory about how the mechanics work is correct). The sizes of the panel puzzles obey a well-tuned distribution; there are heaps of smaller puzzles that can be solved relatively quickly, a fair chunk of larger puzzles, and (thankfully) only a few massive puzzles which, while satisfying to solve, would make for a tedious experience were there any more of them. You are also given the option to mark tiles, which is extremely handy when solving some of the larger puzzles (and they can get very large).

Yet Another Leap of Faith

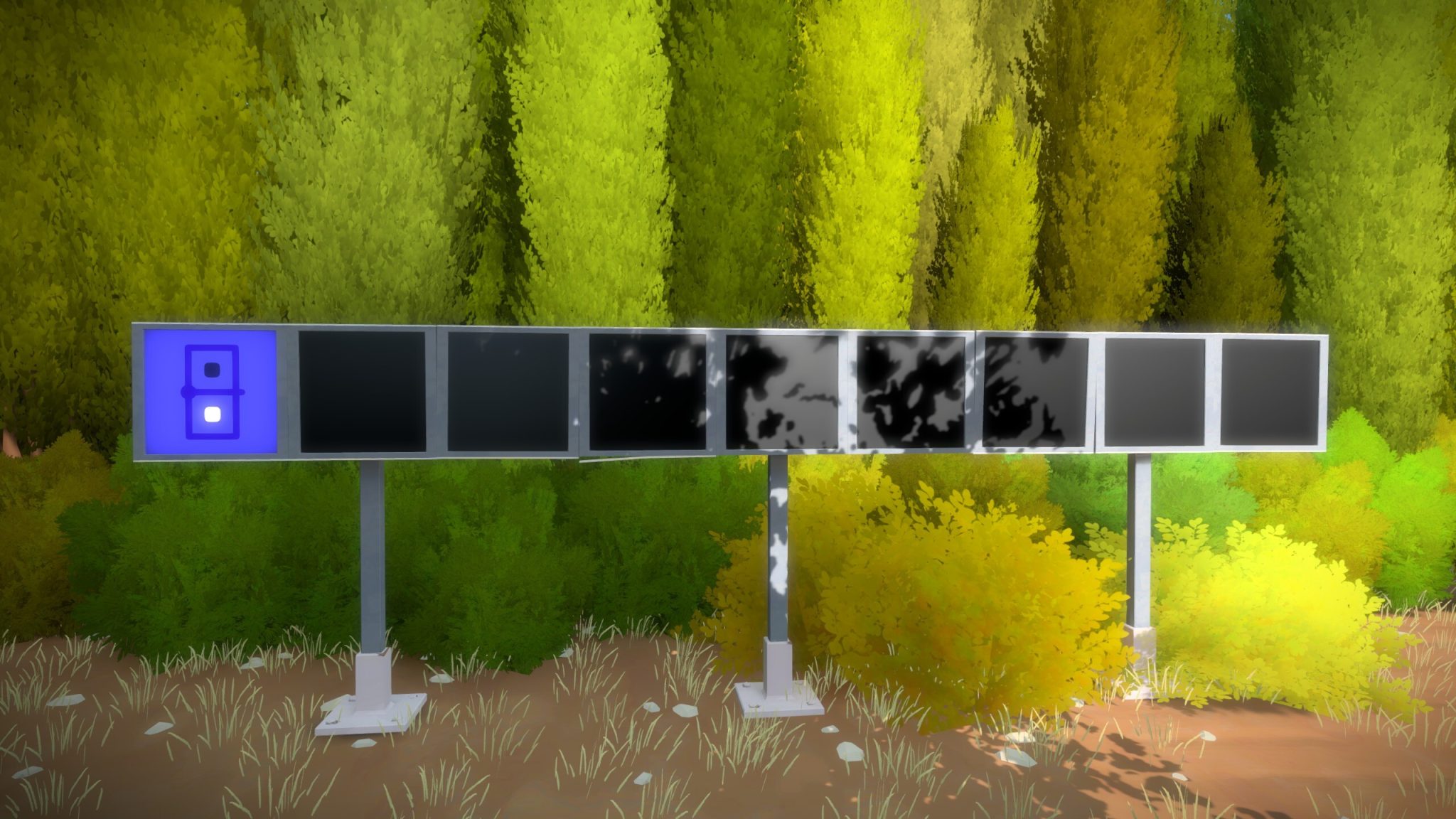

As with The Witness, Taiji relies on player discovery. Mechanics are not explicitly taught, but rather hinted at with examples. However, Taiji doesn’t shy away from explicitly showing the solutions to some of its puzzles in its environment, thereby indirectly showing the mechanic to the player before they solve the puzzle.

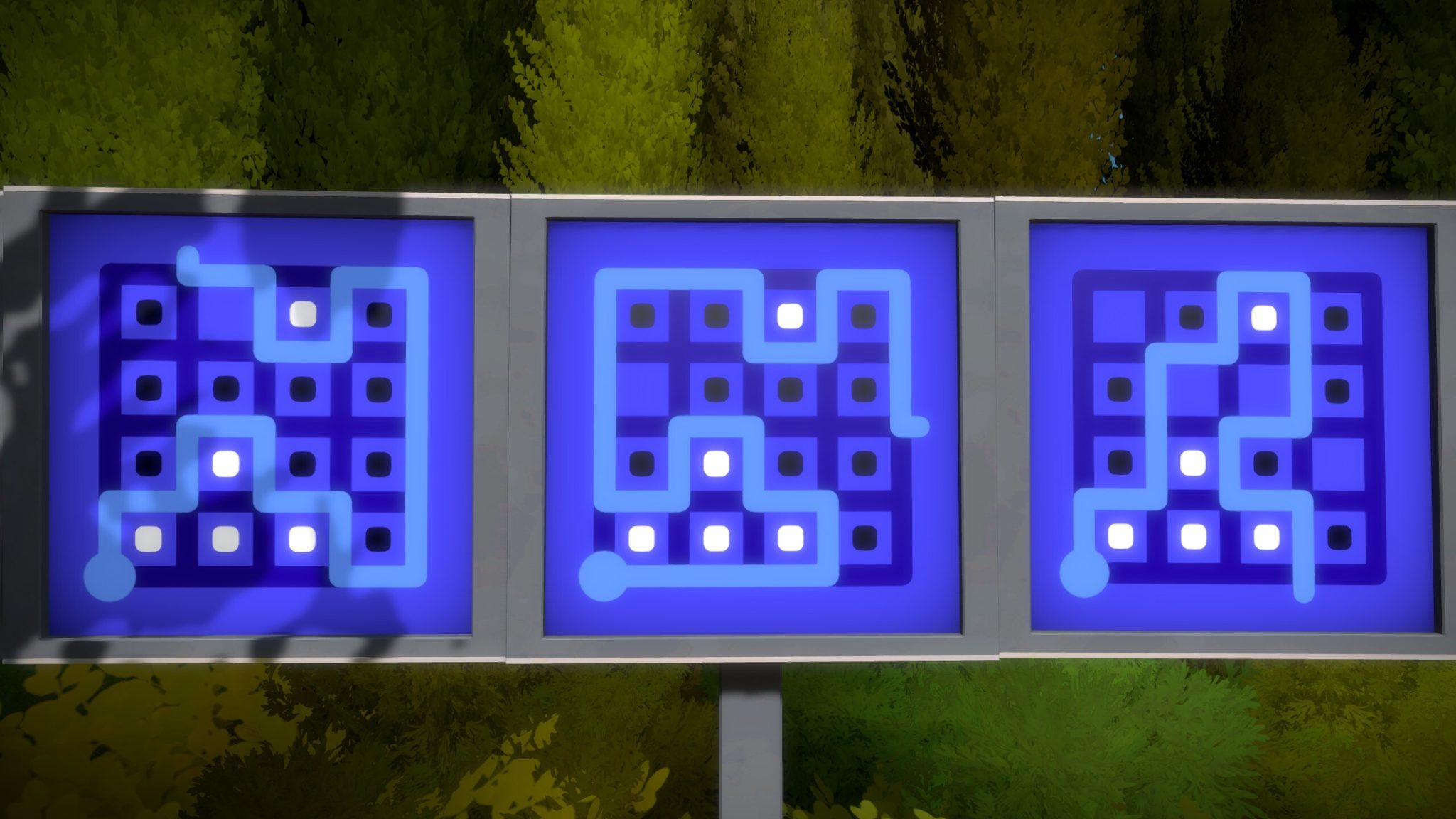

I previously argued that solving puzzles is a delicate leap of faith in the hope that you’ve properly inferred the mechanics, and that the puzzles stay true to said mechanics. As we did for The Witness, let’s go through an example to see this principle in action in Taiji, starting with the introductory puzzles with the white and black blocks.

At first you might be tempted to simply complete the pattern, and this works for the tutorial puzzles. But then you get out into the world and find ever-more complex patterns with black blocks where simply punching in the pattern as displayed no longer cuts it. What’s going on? Have the mechanics changed? Well, no they haven’t changed. It turns out that the rule is not just copying the pattern (and brute forcing some of the unknown blocks). Instead, for each empty space, the correct colour is the non-dominant colour of its adjacent spaces. That is, if the majority of the adjacent colours are white, the square is black (and vice versa). On a macro level, this idea is about partitioning the full grid into regions of white and black squares that satisfies the pattern. In some certain cases these block puzzles can have multiple solutions.

In general,Taiji places a lot more emphasis on its environment. You will need to exploit this fact to unlock the secret ending. Three of its regions rely entirely on gleaning the solution from environmental context. That the starting area is full of floating blocks shaped like the solutions to the puzzles they contain – except for one – is by no means an accident. Taiji also integrates puzzles as a means of movement, even going so far as to temporarily open up and/or close off access to parts of the map. As you’d expect, these puzzles usually have multiple solutions so as to construct pathways that lead to different places.

Taiji’s puzzle density is significantly higher than The Witness, though this is more reflective of the fact that Taiji’s island is itself rather tiny. However, even outside of the primary zones, you’ll just about find puzzles everywhere, in various mine shafts and secret underground rooms. There is even a hidden garden packed to the brim with puzzles; like all good pixel-art games, its entrance is hidden behind a waterfall. As is a common issue with 2D pixel-art games, Taiji does occasionally struggle with communicating depth, especially since there are many hidden rooms and other entrances nestled in the environment. It can sometimes be difficult to discern which paths are actually traversable, and you can often find yourself going around in circles trying to get to places. Thankfully the island is small enough that this isn’t that much of a concern, but if the island was any larger I feel it would at least warrant a minimap outlining where the boundaries are.

Speaking of minimaps, traversing between puzzle zones is made slightly more convenient thanks to a series of teleporters. Each region has a unique pattern that shows up in the teleporter menu. You teleport to your chosen destination by punching in the solution to its corresponding puzzle. It’s interesting to see the similar map style to that of The Witness’ island map. You could argue that the teleporters are a tad unnecessary given the island’s small size (and the player’s Sonic-like sprint speed), but it nevertheless proves useful for late-game backtracking in order to solve some certain meta puzzles…

Apotheosis

There is one very important similarity between The Witness and Taiji that I’d like to think of as, if not an outright homage to The Witness, certainly a shared design tenet. It is not just the similarity of their abstract design, zen-like visuals, segmented world layout and focus on puzzles, but something more fundamental. It’s something I’d argue that is the hook that makes these games work. This hook is the inclusion of both an obvious, implied ending, and a less obvious secret ending that requires a higher understanding of the world in other to ultimately access.

In The Witness, the obvious ending is to descend through the mountain and into the cage (only to watch all your hard work be methodically undone). In Taiji, the obvious ending is to unlock the gate and head on in to enlightenment; its ending scene also uses the motif of a cage (at least in Taiji, when you reload the puzzles remain as they were!)

The secret endings for both games are strikingly similar. Both endings rely on the player to have gleaned insights about the world – particularly its environment – in order to ultimately access. This knowledge must be acquired by the player through the act of simply playing the game, and paying attention. Both endings are located (almost) right next to the starting area. Both require solving an environmental puzzle to access. In The Witness, that’s all you have to do; all that’s left is to meander your way to the exit. Taiji’s secret ending, one you access the cave, is instead locked behind nine additional meta-puzzles, each corresponding to one of the regions on the island. So, off you to go to each little region. What exactly are you looking for? Well, you’ll know when you see it.

For the Joy of Discovery

Therein lies the beauty of Taiji, a world adorned with symbols and motifs, of hidden puzzles and hidden meaning overflowing with energy and discovery. It’s a beauty that needs the abstractness of logic puzzles in order to be properly showcased. It’s a beauty that needs all notions of apparent “meaning” and “purpose” to be completely stripped away in order to be properly appreciated.

And perhaps that joy of puzzle solving – the inherent joy of a “eureka” moment – is part of something more fundamental. Call it curiosity; call it awe. The puzzles are just steps on the journey: means of accessing that higher plane of eureka. The joy of beating The Witness’ challenge is undeniably euphoric. The joy of solving, let alone finding, Taiji’s meta puzzles is undeniable. And the awe at watching a miracle sudoku solution on Cracking the Cryptid is undeniable. So why do logic puzzles elicit such passionate responses? I’d argue that it’s our innate curiosity and joy of discovery. It’s the joy of figuring out the otherwise meaningless symbols that fill the grids and panels of The Witness and Taiji. Yet it’s a joy that doesn’t come easily. It takes something special to evoke it, just as it takes a certain frame of mind to appreciate it.

The Witness tried to get me to notice.

But Taiji taught me to see.