It was the best of times, those halcyon days of middle school in 2011, when evenings were spent conquering empires in Civ V, math class was spent building cities in Minecraft, and weekends were spent roleplaying as Takeda Shingen in Shogun 2, or never asking for it in Deus Ex: Human Revolution. I remember having been in awe of Portal 2 earlier that year, and 2011 shaped to be, as I recall, a golden year for video gaming.

Indeed, on November 11, 2011, life got a whole lot better, when Todd Howard unleashed his Creation Engine and turned an entire generation into dragon-slayers and mountain climbers, or something like that. It’s easy to forget Skyrim’s initial release given how many times it has since been repackaged for console upon console with a Legendary edition, Special edition and soon-to-be-released Anniversary edition, in what can only be described as a case of “beating a dead horse” of the highest order. After all, there were five years between Skyrim and the previous entry Oblivion, and four years between Oblivion and Morrowind, so the Elder Scrolls VI is well overdue. But that’s a story for another day.

I would be lying if I said Skyrim did not constitute a serious chunk of my gaming throughout my teenage years; it is my second-most played game of all time behind only Dota 2. And as this game approaches its tenth anniversary, it’s only fair I give my two cents on the game, its content, its highlights and its flaws. Before starting I should point out that I only played a little bit of Oblivion prior to Skyrim and have not played Morrowind, and while this review is not intended to focus too much on comparisons I will make a few comments about overall trends. For a comprehensive review of all of these games in the context of the Elder Scrolls series at large, I highly recommend NeverKnowsBest’s three-part series.

Context, Premise and Setting

The Elder Scrolls series is a long-running, open-world RPG series that commenced with the release of Arena in 1994. Key highlights of the series often include large open worlds, extensive lore and open-ended quest design. At least, most of these were key highlights. The trend with many modern games is often on simplification (or casualisation). Remember the classic days of Call of Duty when actual missions felt like genuine uphill battles rather than mindless action? The Elder Scrolls is not immune to this. Many RPG elements have been streamlined to the point where Skyrim is more an action-adventure game mechanically compared to an RPG. That Skyrim is, in this sense, a much more casual and “popularised-for-the-mainstream” game is a point of contention for veterans, and while this broader appeal has undoubtedly paid dividends in terms of commercial success and continued revenue even to this day, the game itself is left feeling rather superficial and narrow. I suppose this was never a concern for me when I was a teen, but looking back on the game now I can see where a large part of the “RPG” in Skyrim is really up to your personal immersion, and not through any explicit mechanics in the game. I’ll return to this point more in later sections, but for now let’s briefly summarise what Skyrim is about.

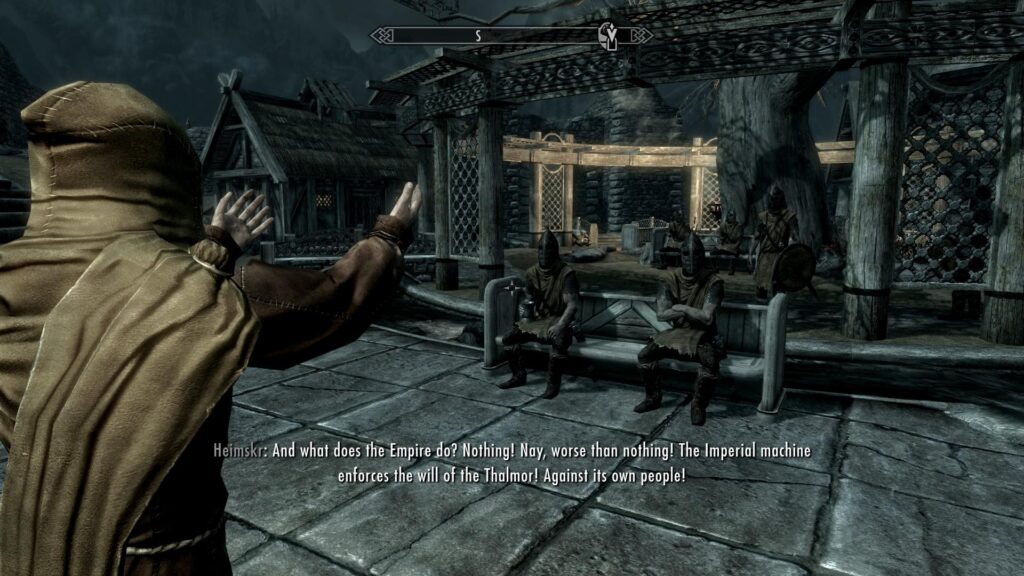

The game is set in the province of Skyrim, in the northern part of Tamriel, roughly 200 years after the events of the previous game. It is the 201st year of the Fourth Era, and dragons have returned to life. The Imperial Empire has been severely weakened after the Great War and the signing of the White Gold-Concordat which, among other things, restricts the worship of Talos – the deification of Tiber Septim, first Emperor of Cyrodiil. A certain Ulfric Stormcloak demands free worship of Talos and independence from the Empire, and triggers a civil war after challenging and killing High King Torygg. It turns out that all these events, in addition to those from previous games, satisfy the prophecy of the Last Dragonborn. And so, the wheel turns to you.

The Main Quest

Like most Elder Scrolls games, you start off as a prisoner. You are captured alongside Ulfric Stormcloak and several Stormcloak rebels and are being escorted to Helgen to face execution. Just as you lay your head on the block, a dragon attacks the village. You eventually escape – following either one of the rebels or one of the Imperials – and make your way to the nearby town of Riverwood, where the locals urge you to continue north to Whiterun and inform the Jarl about the attack. So, you make your way to Whiterun, where the Jarl introduces you to his court wizard Farengar who instructs you to retrieve “an ancient stone tablet that may or may not actually be there” from the Nordic ruin Bleak Falls Barrow, located just near Riverwood.

By the way, just about every quest in Skyrim can be boiled down to a fetch and/or delivery quest, or at the very least a quest where you need to go clear out a dungeon and complete some objective in that dungeon (find a word of power, kill the bandit leader, retrieve an item, etc). This core game loop is clearly quite simple, but is an extremely effective dopamine rush that’s fine-tuned to keep the player engaged and make the player feel rewarded. Dungeon design is centred around the player rather than the larger environment, and thus tends to sacrifice realism for convenience, such as with shortcut exits at the end of just about every dungeon that so happen to lead directly to an exit.

Anyway, you go to Bleak Falls Barrow and retrieve the Dragonstone, as well as learning a word of power along the way. You return to Farengar, when news breaks that a dragon has been sighted nearby. So you head on out with Irileth and a handful of guards in tow to the Western Watchtower, and slay the dragon. To everyone’s surprise, you absorb the dragon’s soul, which leads some of the guards to believe you are Dragonborn. Turns out that word of power you learnt back in Bleak Falls Barrow, fus, is a shout – a type of spoken magic in the language of the dragons. This draws the attention of the Greybeards, who summon you to their monastery, High Hrothgar, located on the side of the tallest mountain in Tamriel, the Throat of the World.

After climbing the 7,000 steps (the actual number is more like 700) up the mountain, the Greybeards teach you two new words of power: ro, the second word of Unrelenting Force, and wuld, the first word of a new shout, Whirlwind Sprint. The ask you to do another fetch quest, this time to return the Horn of Jurgen Windcaller from Ustengrav. Once you get there, the horn is missing, with only a note left behind asking you to book the attic room at the inn in Riverwood. You head on back to Riverwood to an innkeeper named Delphine, and ask for that exact room. Turns out she’s a member of the Blades, ancient dragonslayers and protectors of the Dragonborn Emperors, since driven into hiding by the Thalmor, a faction of ultranationalistic high elves who believe in elven supremacy and see it as their birthright to rule all of Tamriel. She wants proof that you’re Dragonborn, and suggests travelling to Kynesgrove, where she believes the next dragon will awaken from. You head to Kynesgrove where the same large, black dragon you saw at Helgen revives another dragon from its burial mound, before flying away. After slaying the revived dragon, Delphine agrees to spill the beans on everything she knows. Be sure to return the horn to the Greybeards to learn the final word of Unrelenting Force, dah.

To learn more about the dragons, she suggests infiltrating the Thalmor Embassy during a soiree held by Elenwen, the Thalmor Ambassador to Skyrim. This goes about as well as can be expected, but after taking several dossiers it becomes clear that the Thalmor are just as clueless. They are, however, searching for Esbern, a Blades archivist, who they believe to be hiding in Riften. It’s here at Riften that you are exposed to the first factional quest with the Thieves Guild, which involves stealing a ring from a market stall and planting it in someone’s pocket. As for the main quest, you head into the Ratway and find Esbern in its lower reaches. The two of you escape and return to Riverwood for a brief reunion with Delphine, before it’s on to the Karthspire in search of an ancient Blades temple believed to contain Alduin’s Wall, a bas relief displaying the Blades’ knowledge of Alduin’s defeat and future return. It turns out that Alduin was defeated by a shout. This leads you back to the Greybeards, of whom the Blades are no great friends of (and vice versa), where you ask Arngeir about a shout that can defeat a dragon. Arngeir is initially angry but soon relents, and insists you meet their leader, Paarthurnax, atop the Throat of the World. He teaches you the Clear Skies shout in order to clear the path up the mountain, where upon arriving at the summit you find out that Paarthurnax is a dragon.

After some philosophical musing, Paarthurnax suggests using an Elder Scroll to peer back in time through the “time wound” to the moment when Alduin was banished. It’s off to the College of Winterhold to inquire about an Elder Scroll. You are led to the remote outpost of a mad scholar, Septimus Signus, who believes he has found the location of a forgotten scroll. He gives you two items, “One edged, one round”, then sends you to the Dwemer ruin Alftand. The items are an attunement sphere, used to unlock the staircase to Blackreach, and a lexicon, with which to inscribe the contents of the Elder Scroll.

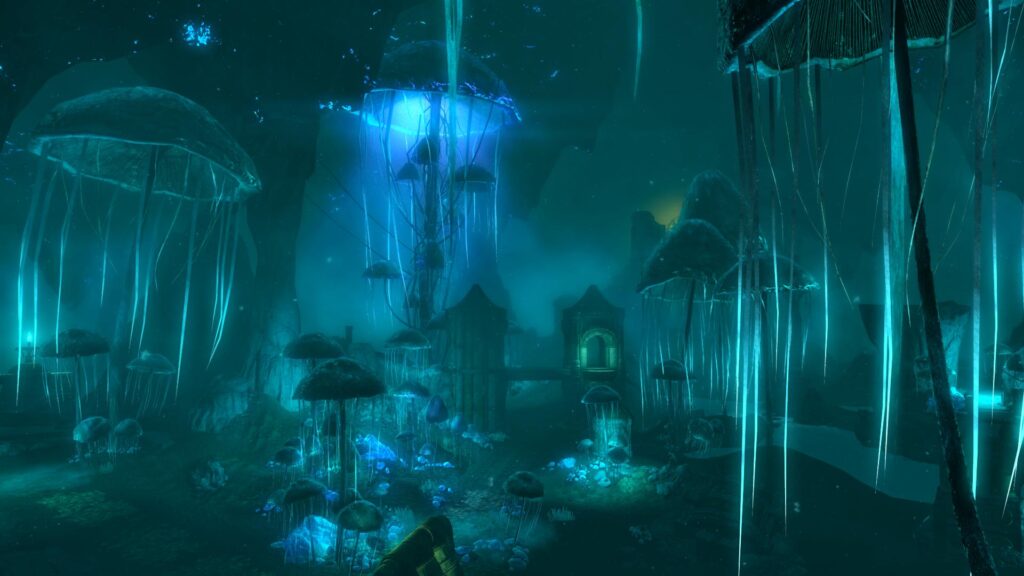

Blackreach is a massive underground cavern containing various Dwemer sites, since overrun by Falmer (as well as several Nord thralls). It’s also home to a dragon (summoned by shouting at the large overhead light). There’s some interesting side objectives here, like collecting 20 samples of the rare crimson nirnroot. Blackreach is by far a fantastic place to explore, with bioluminescent fungi and heaps of soul gems able to be mined. Head on up to the Tower of Mzark to collect the scroll and inscribe the lexicon for Septimus. Completing the rest of Septimus’ quest leads to a fancy Daedric artefact, though this is not part of the main quest.

Return to the Throat of the World to learn the Dragonrend shout from the ancient Nordic heroes who had banished Alduin. After having peered back in time, Alduin will appear and attack. Once you “defeat” him, it turns out he cannot be fully slain, and instead flies off to presumably regain his strength. Now it’s a case of figuring out where he went, and to do so Paarthunax suggests trapping a Dragon at Dragonsreach, the palace in Whiterun, which was originally designed to house a captive dragon. The Jarl of Whiterun naturally objects, and if the Civil War is still raging you’re instructed to get the two sides to agree to a truce. The negotiations take place at High Hrothgar and can lead to some fireworks and colourful language as both sides push for concessions. With the temporary truce arranged, Esbern gives you the name of a dragon, Odahviing, to summon and lure to Dragonsreach.

Once you’ve captured the dragon, he will offer to fly you to Skuldafn, a large and otherwise inaccessible Nordic ruin complex that contains a portal Alduin uses to travel to Sovngarde, the Nordic land of the afterlife, where he feasts upon the souls of the deceased to regain his strength. Head on over to Skuldafn for yet more rinse-and-repeat dungeon crawling, and pop on through the portal.

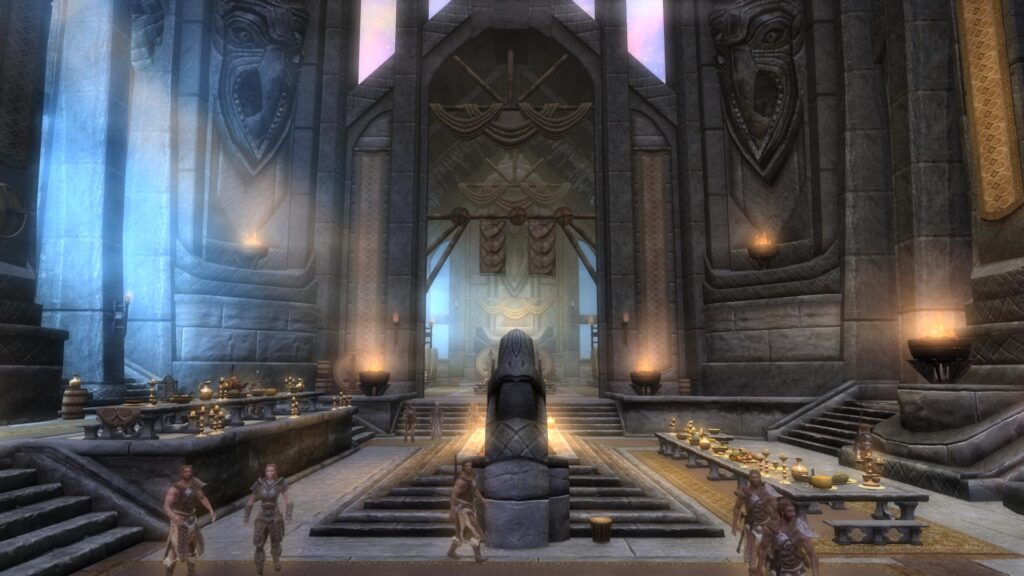

You must head on to the Hall of Valor (basically Skyrim’s version of Valhalla) to meet with the spirits of the three ancient heroes to face Alduin in battle. The battle comes, you slay Alduin and… that’s it! Overall, the main quest is the strongest quest line in the base game, although it is a strongly linear experience, and is dominated by fetch quests.

Dungeons, Loot and Economy

Skyrim’s dungeons come in multiple flavours, though the most notable are the Nordic ruins and Dwemer ruins. Dwemer ruins have their usual characteristic, steampunk aesthetic, while Nordic ruins are quite dull. It doesn’t help that most Nordic ruins are fairly identical, both in terms of the types of enemies you’ll encounter, as well as their overall layouts. Nordic tombs tend to have rotating pillar puzzles, which are mostly just an annoyance as they do nothing to challenge the player but rather waste time. There are various other types of dungeon including bandit camps, mines and caves. Further points of interest include towers, lookouts, Daedric shrines, dragon lairs, orc strongholds, monuments, glades, huts/shacks, standing stones (which grant passive effects) and a whopping two lighthouses!

The loot in Skyrim is not particularly noteworthy, if anything the word loot in the context of Skyrim refers to the mod loader and not the game itself. That said, Skyrim does have several tiers of armour and weapons, heaps of alchemy ingredients, potions and scrolls, various gems and other miscellaneous items, and over a hundred books. While you can go and clear out every chest in every dungeon, it’s often not worth it. Skyrim has possibly the easiest economy of any game I’ve played, and it’s near-impossible to run out of money. If anything, merchants will regularly run out of money to buy things off you. When money becomes meaningless, so too inevitably does loot, and so there’s no real incentive to invest in skills like smithing and enchanting when you can almost always acquire such items through looting or purchasing with your piles upon piles of gold.

Ambience, Atmosphere and Aesthetic

Skyrim is a beautiful game, and while it’s vanilla (un-modded) graphics are dated by today’s standards, the gorgeous environments are great, and it’s often hard to resist the temptation to stop and take a screenshot of a wonderfully sculpted vista. There is also great diversity in environments, from the aspen forests of The Rift, to the dense pine forests of Falkreath, to the juniper bushes of The Reach, to the tundra of Whiterun and to the snowcapped mountains of Winterhold. Weather and the day-night cycle are both wonderfully executed, with gorgeous sunsets and sunrises, and subtle transitions to rain and snow.

It would be wrong, despite recent events, not to credit much of Skyrim’s magnificent ambience to Jeremy Soule and his incredible soundtrack. To me personally, sound design and music are especially strong (and often overlooked) parts of game design, capable of evoking strong emotion and helping with pacing. Exploration in Skyrim is great fun, as you can lose yourself in both the environment and the music. Fundamentally, however, this is merely exploration for the sake of exploration.

One of the appealing aspects of the worlds of the Elder Scrolls games is simply their size, and the ability for the player to explore almost all of it, in a sense getting to experience another world. Unfortunately, most of Skyrim’s actual gameplay takes place in linear dungeons, far removed from this gorgeous open world. Apart from the Treasure Hunts and very few side quests, there is no real need for the player to explore, merely to instead follow quest markers to the next dungeon. To me this is a missed opportunity, as it’s clear a lot of work went in to crafting this world. It basically feels like walking back and forth through the Sistine Chapel, only to crawl around in vents Deus Ex style completing dungeons and looking for items, then walking back to return or sell said item to some NPC. That doesn’t mean that dungeons don’t have good looking environments buried within them, but it’s just a shame how much relative time is spent inside them.

Lore, Design and Substance

Skyrim draws on well over 20 years of accumulated Elder Scrolls lore, replete with millennia of history. Most of this lore is not to be found in Skyrim itself, but rather either having played previous games, or instead through the two major online wikis. Books nevertheless provide an overview of major events, significant individuals, history, culture, religion, fables, and lusty Argonian maids. NPCs will also provide some insights into lore and both historical and cultural background. While this is not the sort of game for extended exposition, it’s good to have dialogue options to learn more about the world of Skyrim, even if most players simply won’t bother. Another part that makes Skyrim unique is the Dragon language, a functional conlang written in the so-called Dragon script (essentially an extended alphabet), which forms the basis of the Thu’um (or shouts magic).

As aforementioned, Skyrim’s game loop is really one of going to a linear dungeon to carry out some trivial objective. Skyrim also uses a “radiant quest” system which picks a random location for some given fetch quest. The ubiquity of fetch quests may lead one to conclude that Skyrim is just a dressed up single-player MMORPG, and that may well be true. But at least a MMORPG has meaningful character development and a rich variety of skills to benefit many different playstyles. Unlike previous entries in the series, Skyrim forgoes manually assigning skillpoints, and instead starts off with a base skill level in every skill (modified depending on starting race). Each skill has a perk tree. As you level up skills, you level up your player level. Each new player level grants one perk point to invest in some perk tree. I should stress here that most of perk trees are generally useless, especially Lockpicking (you can pick any lock from base level). When your player level increases you can choose to increase your health, magicka or stamina stats. But this all feels very superficial. Level 30 doesn’t feel any different to Level 3, insofar as you perhaps don’t need to chug as many potions during a fight. The only things that are noticeably tied to player level is the type of enemies and quality of loot.

You could say that Skyrim lacks a lot of substance. It is, after all, a surprisingly linear game, with the only “open world” aspects being the actual world itself, and the fact that you can choose to go off and do any quest you want at any time. But when it comes to the quest design itself, it’s all very linear. This is why, in my opinion, Skyrim is not an RPG. Not only do RPGs allow for much more fleshed out characters, an extremely important aspect of RPGs is emphasis on player choice, especially allowing for multiple ways to achieve some given objective. Let’s take the first battle with Alduin, after he flies off. The objective is to find where he went. In Skyrim, you’re pretty much roped into having to capture a dragon at Dragonsreach. What if you could instead find Skuldafn another way? Also, when Septimus gives you the attunement sphere, why does he insist you go to Blackreach via Alftand when there are other Dwemer ruins that lead there? Wouldn’t it be more immersive for him to give you the sphere, say something along the lines of “the bottom level, where stairs are locked, etched in stone, the blackest rock.” Then, you’d go pick up and read a copy of Dwemer Inquiries Vol. III, flick to the final paragraphs which mention a strange inscription meaning “Blackest Kingdom Reaches” found at the bottom of Alftand, Irkngthand and Mzinchaleft, then head to one of those Dwemer ruins of your own accord and unlock the stairs? Wouldn’t that feel so much more rewarding? Alas, quest markers.

Overall, there are few meaningful hard choices or opportunity costs in Skyrim. After all, anyone can be a competent mage, archer or warrior, mastery in one does not preclude the other, you can be anything you want to be. Sometimes, in a game where you can do anything, it can feel like you’ve done nothing. Factions lose meaning when you can become the head of every single one. And while there’s nothing inherently wrong with this sort of mindless power fantasy, you don’t exactly walk way with a sense of genuine achievement.

Factional Quests

Speaking of factions, Skyrim has fewer than its previous entries. There’s the Companions (essentially a fighter’s guild), the College of Winterhold (mages’ guild), the Thieves Guild, the Dark Brotherhood and the Civil War. There are a few minor factions with only a handful of related quests, namely the Blades and Bard’s College.

In the Civil War you can side either with the Empire and the Stormcloaks. After another bloody fetch quest (Jagged Crown), the first major battle is either the defence or siege of Whiterun. From here you simply follow orders, going from fort to fort, to capture territory until only one hold is left, either Solitude or Windhelm. Thus commences the final battle. Apart from changing some of the Jarls and replacing guards in captured cities with soldiers, there are no other major changes after completing this quest.

The College of Winterhold quests are concerned with the recovery of a mysterious and powerful artifact – the Eye of Magnus – which the Thalmor representative to the college, Ancano, tries to harness for himself. Despite being a quest line supposedly focused on mages, there’s fairly little actual application of magic, and instead you’re mostly trudging around Nordic tombs again.

The Companions quests are concerned with lycanthropy. Again, it starts with a fetch quest to reassemble an ancient sword, and most of the quest line is spent fighting against The Silver Hand, who are werewolf-hunters. It’s strange that the Companions put faith in codes of honour, and that so much time is spent exterminating those who would otherwise have hunted werewolves since some members actually are werewolves. It’s quite underwhelming, to be honest. At least you get to meet the spirit of Ysgramor in the final quest, and can gain the ability to smith Nordic weapons and armour at the Skyforge.

The Thieves Guild quests are mostly concerned with daedra worship rather than actual thieving. Correction, there are a lot of grindy thefts required to actually become the leader of the Thieves Guild in what can only be described as one of the laziest reliances on the radiant quest system in the game. That said it is the faction I like the most as the whole Nightingale stuff is quite cool, plus I feel the story is a tad more polished than in the other faction quests.

Initially, the Dark Brotherhood is more concerned with Astrid’s insecurity more than anything, but the main event is the assassination of Titus Mede II, which is not actually all that exciting. To join, you first need to fulfill Aventus Aretino’s request to remove a particularly cruel headmistress at the Riften Orphanage. Not long after you’ll get the famous “we know” handprint note from a courier. Upon receiving this and going to sleep, you’ll wake in an abandoned shack and must perform a little test for Astrid. It goes downhill from here. My memories of these quests don’t stick with me as strongly as others as they are fairly unremarkable.

Dawnguard

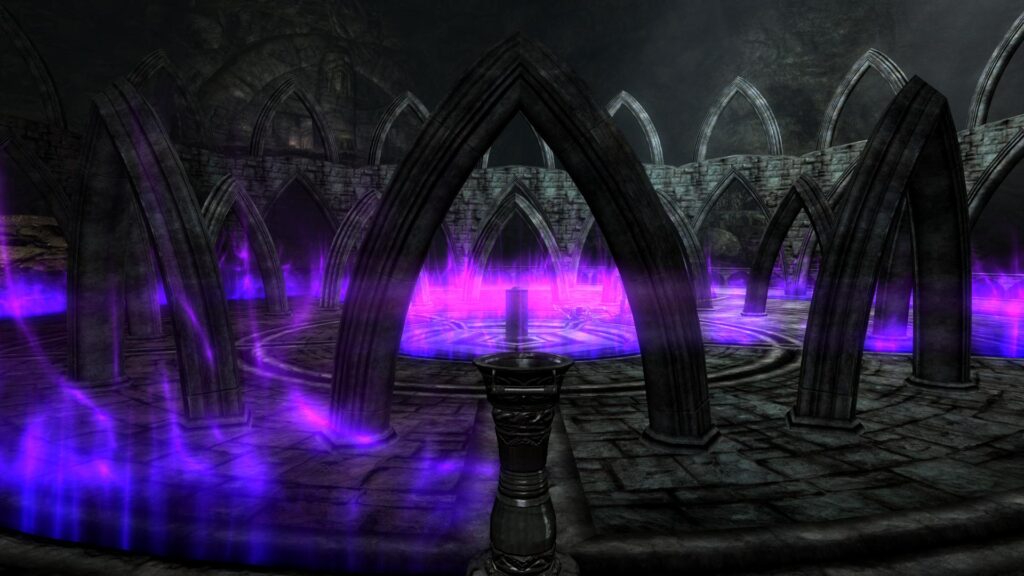

Skyrim’s first DLC expansion is Dawnguard. It is easily the best addition to the game, and my favourite quest line. The expansion adds the Dawnguard faction, headquartered at a fort of the same name, a group of vampire hunters led by Isran. You are encouraged to check the place out by one of their members. Head on over and you’ll watch Isran have a heated conversation with one of the last remaining Vigilants of Stendarr (also vampire/daedra hunters), whose headquarters were decimated by a vampire attack. You then head off to this cave, which is supposedly of great importance to the vampires. It’s here that you start to see the new vampire aesthetic, particularly the vaulted ceilings, gargoyles and smooth stonework, which clearly contrasts with the Nordic ruin aesthetic.

Sure enough, you find a woman entombed in a central chamber, carrying an Elder Scroll. She is Serana and, not just any vampire, but a Daughter of Coldharbour; a pure-blooded vampire. Turns out she’s been hidden away for a very long time, and she requests you bring her to her family home, which is a giant castle of vampires located off the coast of Haafingar. Once you get there, you are confronted by her father, Lord Harkon, who gives you a choice. Join them, and become a vampire, or be banished (and side with the Dawnguard).

There are only some slight differences in terms of the next few quests depending on whether you join the vampires or the Dawnguard, but ultimately your next objective is to find a Moth Priest to read Serana’s scroll. This then reveals part of a prophecy called the Tyranny of the Sun, however more Elder Scrolls are required in order to fully decipher it. Serana notes that her mother, Valerica, also has a scroll. So, it’s off to Castle Volkihar to search for Valerica. This leads you on a journey to the Soul Cairn, an otherworldly plane of Oblivion from where necromancers can draw immense power through bargaining with the Ideal Masters, often with disastrous results. The Soul Cairn, and its associated lore, is wonderfully executed, and it’s great fun to explore. Once you collect Valerica’s scroll, you return to the Moth Priest only to find out he’s been blinded by his haste to read the scroll. There is, conveniently, a so-called ancestor glade in southern Skyrim, home to ancestor moths, wherein one can perform a ritual to read Elder Scrolls. This is yet another beautiful location – and the scene when reading of the scrolls is absolutely marvellous. You’re led to a remote cave in search of Auriel’s Bow, and this leads to, in my opinion, the best quest in the game.

I’m not normally moved by video games, but Touching the Sky gave me chills. A large part of that is the gorgeous serenity of the Forgotten Vale, coupled with the hauntingly beautiful, mournful soundtrack that plays when you wander through its Falmer-infested gorges, knowing what the Chantry of Auri-El meant to the Snow Elves. The full weight of history and culture bears down on you as you journey from wayshrine to wayshrine. It’s a powerful experience. You eventually confront the creator of the prophecy, who intends to use the blood of a Daughter of Coldharbour to seek revenge on a god. Anyhow, all is resolved in a surprisingly easy fight, after which you acquire Auriel’s Bow. Now to challenge Lord Harkon (and, obviously, be victorious).

The Dawnguard quest line is very well polished, and a large part of its success and why I remember it so vividly is because of the variety of locations, from the beauty of the Forgotten Vale, to the strangeness of the Soul Cairn. Serana is also a big reason, as one of the few genuinely enjoyable NPC companions. A lot of work clearly went into the voice acting and dialogue, and it shows in how the relationship matures as the story progresses.

Hearthfire, Dragonborn and Solstheim

The second DLC, Hearthfire, allows the player to purchase land and construct a homestead. I won’t say all that much here, as this is mainly a side activity, but it’s a welcome edition nevertheless.

Dragonborn is the third DLC and adds the island of Solstheim. Unlike Dawnguard, the main quest line in Dragonborn is considerably shorter. It revolves around the return of the first Dragonborn, Miraak, who has enthralled the citizens of Solstheim to build various temples in his honour, including around several magical stones. A large chunk of the quests here also involve journeys into the Hermaeus Mora’s realm of Apocrypha via reading several Black Books in search of a way to defeat Miraak. One of these Black Books lies at the end of a somewhat memorable journey through a Dwemer ruin with the Telvanni wizard, Neloth. Turns out Hermaeus Mora is after the knowledge of the Skaal, the native monotheistic peoples of northern Solstheim, so he gives you the remaining word of the power of the “Bend Will” shout in exchange for the life of the Skaal Village Elder. With that, you finally return to Apocrypha to challenge Miraak and end him once and for all. Actually Hermaeus Mora steals the kill. But nevertheless, Miraak is vanquished and you can finally absorb dragon souls properly.

Sure, Apocrypha has a distinct Lovecraftian vibe to it, but I find its environments and level design to be far too repetitive. Fighting the same two enemies also gets very boring very quickly. There is one big plus of this expansion, namely Solstheim itself. It’s great to walk around a Dunmer city and the ash wastes throughout the southern portion of the island, with Red Mountain off to the distance. It’s great to see netch wandering the barren landscape, and also to hear songs from Morrowind as part of the soundtrack.

Modding

No game is synonymous with modding more than Skyrim. I personally have not modded Skyrim that much, save for SkyUI, the unofficial patch and the Campfire mod, but there are many more out there, from total conversions to graphical overhauls to entire new expansions. Bethesda, for better or worse, could not help itself to join in the fun. This began with the “blink and you miss it” paid mods experiment on Skyrim’s Steam Workshop in 2015. The plan would have allowed modders to sell their creation on the Steam Workshop. As expected, the fan backlash was swift and universal. So swift that the initiative was pulled soon thereafter and, seemingly, never spoken of again. Paid mods returned a second time ’round, but this time branded as the Creation Club. Ten years on, the modding scene is as strong as ever and continues to offer outstanding content for free.

Celebrating Ten Years

Despite its flaws, Skyrim is nevertheless a fun game and deservedly sits among the most notable games of 2011, let alone of all time. It remains, for me, one of the most immersive single-player games, topped only by The Witcher 3. I only hope that The Elder Scrolls VI can live up to the hype, but given the trend of the series it is likely the next entry will see a further streamlining and simplification of game mechanics. The Elder Scrolls probably won’t ever be a proper RPG again, but that doesn’t mean I’m not looking forward to roaming its wilderness once more.